A Pinot Noir Awakens in Alsace

What does Alsace’s new red cru signal for Pinot Noir?

What does Alsace’s new red cru signal for Pinot Noir?

Dutch-native Benjamin Roelfs is a sommelier by training and passionate wine writer. He has a deep affection for the wines of Alsace and is currently writing a book on the subject. His articles can be read in jancisrobinson.com, Falstaff and The Drinks Business. @benjamin_on_wine.

Trink Magazine | Are PIWIs or grape hybrids our viticultural future as the climate crisis makes winegrowing more, not less, challenging? By Christoph Raffelt

A handful of Weinheim visionaries are reshaping the future of German wine in the country's largest winegrowing region with lessons from the past.

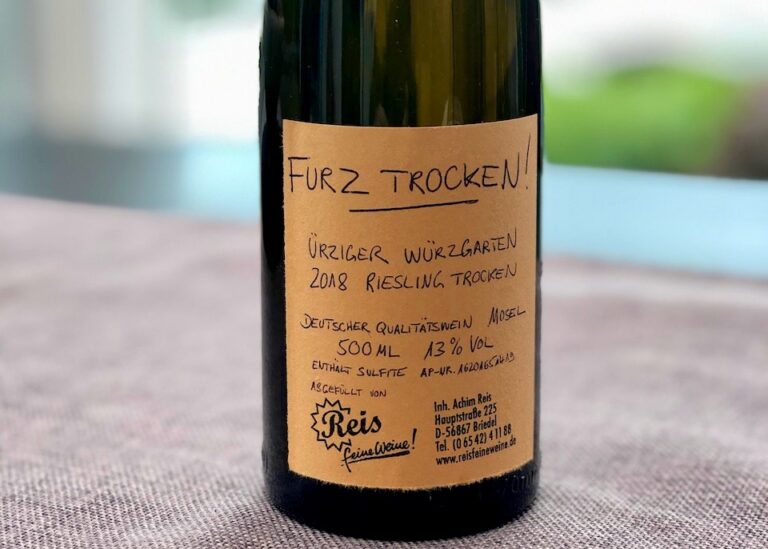

The dark wit of Berlin. Dangerously low water levels in the Rhine River. Black bread. Germany does trocken like few others. And then there’s the wine. Despite its reputation as the land of Blue Nun, more than 60 percent of the wines made in Germany are dry. And within that 60 percent, there are discernible levels of dry, drier, and driest. So dry, in fact, that there’s a strangely specific word for it. (Of course there’s a word. It’s Germany. There’s always a word.) Furztrocken. Fart Dry. Literally. As difficult to grasp as I find a term like feinherb, it’s Kinderspiel when compared to furztrocken. Then again, mindset…...

Gerhild Burkhard, founder of the International Sparkling Festival, reveals everything you've always wanted to know about sekt (*but were afraid to ask).

Terry Theise. Until quite recently, I would have written “an importer of German and Austrian wine who needs no introduction.” But over the past year, the axis of wine, not to mention the world, has shifted. A slew of new wine lovers might just need to be brought up to speed on this pioneering champion of “umlaut-bearing wines” (a term Theise coined long before we or anyone else). Theise fell for German wine and wine culture while living in Munich in his 20s. When he returned to the U.S. in the early 1980s, he brought this zeal back with him. He…...

Abandoned vineyards and hard work are opening opportunities for young growers to try their hands a wine growing and making on the Mosel.

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today