Veritable Vernatsch in Alto Adige

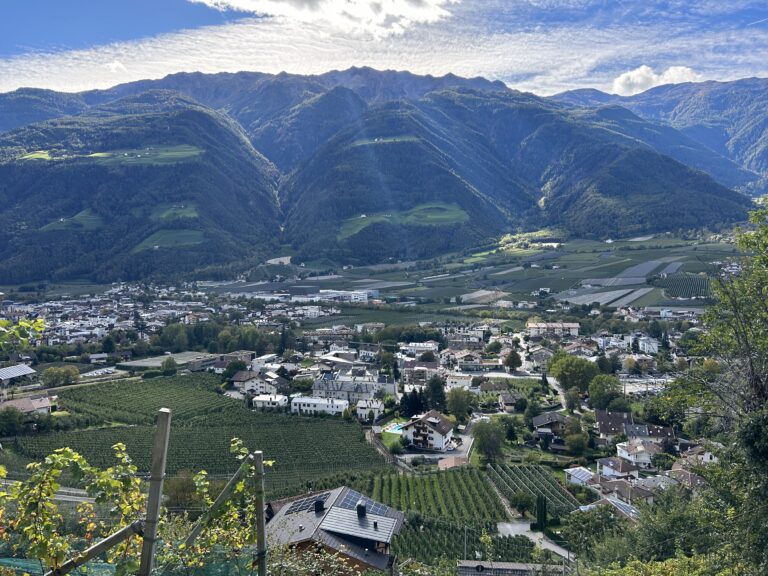

For centuries, the grape variety Vernatsch has been both flagship and albatross around the neck of Italy’s northern region of Alto Adige-Südtirol. In this final installment of his three-part series, Simon Staffler looks closely at DOC Alto Adige and posits the question: Why Vernatsch? “Vernatsch is unique in the world,” says Martin Pollinger, winemaker at Weingut Eichenstein. The estate is located 400 meters above the city of Meran, and Pollinger is part of a new generation of winegrowers and winemakers who are finding their way back to South Tyrol’s flagship variety. Surrounded by vines, Meran makes up the westward start of the…