Happy Wine Hikes in Alto Adige: 7 Rules

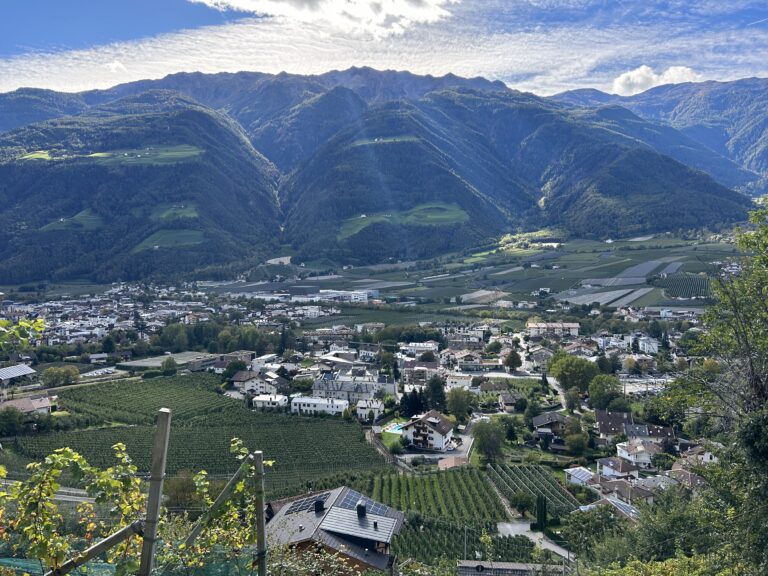

Wine and hiking expert Ellen Wallace guides readers to the green heart of Alto Adige with stops at biodynamic winery Manincor and leading cooperative Kellerei Kaltern.

Wine and hiking expert Ellen Wallace guides readers to the green heart of Alto Adige with stops at biodynamic winery Manincor and leading cooperative Kellerei Kaltern.

Ellen Wallace is the author of Wine Hiking Switzerland, a selection of 50 hikes and 50 wines, to be published 1 September 2022 by Helvetiq, in English, German and French. Ellen is an American-raised Swiss who lives high in the Alps. She is the author of the introductory book Vineglorious! Switzerland’s Wondrous World of Wines and she publishes an independent blog and newsletter in English whose main focus is journeying through the landscape (wines, vineyards, people, history, culture) of Swiss wines, to make these more accessible to wine-lovers in Switzerland and outside the country. Ellen is also a regular presenter of Swiss wines to groups and clubs, in English. She has judged at the Mondial de Bruxelles, Mondial des Pinots, Mondial des Merlots and the national Grand Prix des Vins Suisses.

For centuries, the grape variety Vernatsch has been both flagship and albatross around the neck of Italy’s northern region of Alto Adige-Südtirol. In this final installment of his three-part series, Simon Staffler looks closely at DOC Alto Adige and posits the question: Why Vernatsch? “Vernatsch is unique in the world,” says Martin Pollinger, winemaker at Weingut Eichenstein. The estate is located 400 meters above the city of Meran, and Pollinger is part of a new generation of winegrowers and winemakers who are finding their way back to South Tyrol’s flagship variety. Surrounded by vines, Meran makes up the westward start of the…...

Trink Magazine | The 12 winegrower cooperatives of Alto Adige produce some of the finest wines in Italy, if not the world. it's a part not only of the region's history but also its DNA, Susan gordon reveals why.

A new generation of growers is breathing life into wines of Südtirol-Alto Adige.

Trollinger was long decried as a poor excuse of a wine. Increasingly, growers and drinkers beg to differ.

TRINK Magazine | Japanese Tonkatsu proves an ideal pairingwith 2018 Alto Adige's Kettmeir Pinot Bianco.

Südtirol-Alto Adige winegrowing has already exerted tremendous energy in re-inventing itself. But as has become ever clearer, that was only step one. The second is yet to come.

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today