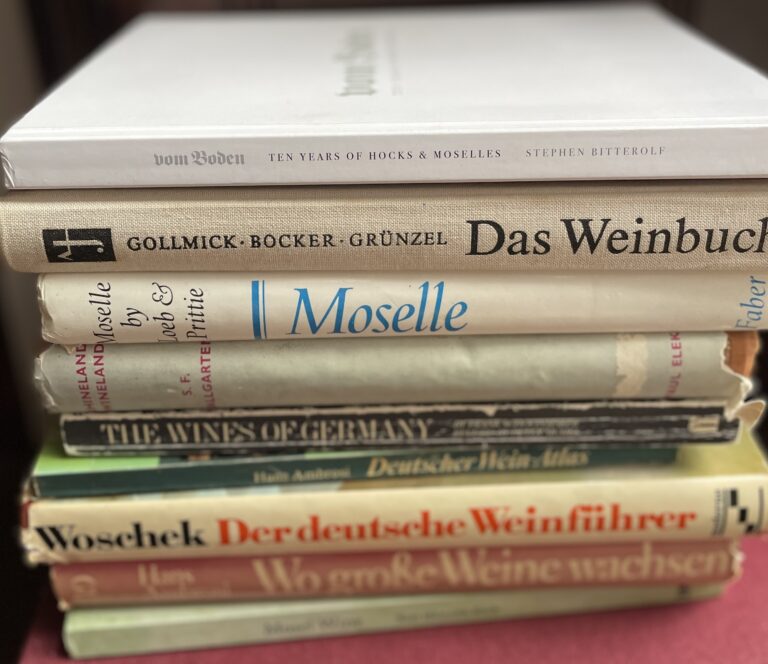

Letter to My Younger Somm Self

Don’t let anyone tell you those rocks are a waste of time. Twenty-five years from now, sitting in a Koblenz classroom on your first day of wine school, you will be grateful for each and every one of them. Because there in the heart of German wine country, those stones and their secrets — though you don’t know it yet — will be the foundation keeping you steady among your more experienced classmates, those vintners’ sons and daughters who boast seven, ten, 15 generations in the business, and counting. All while you are still trying to locate the Mosel on…