A New Book Probes the Heart of German Wine

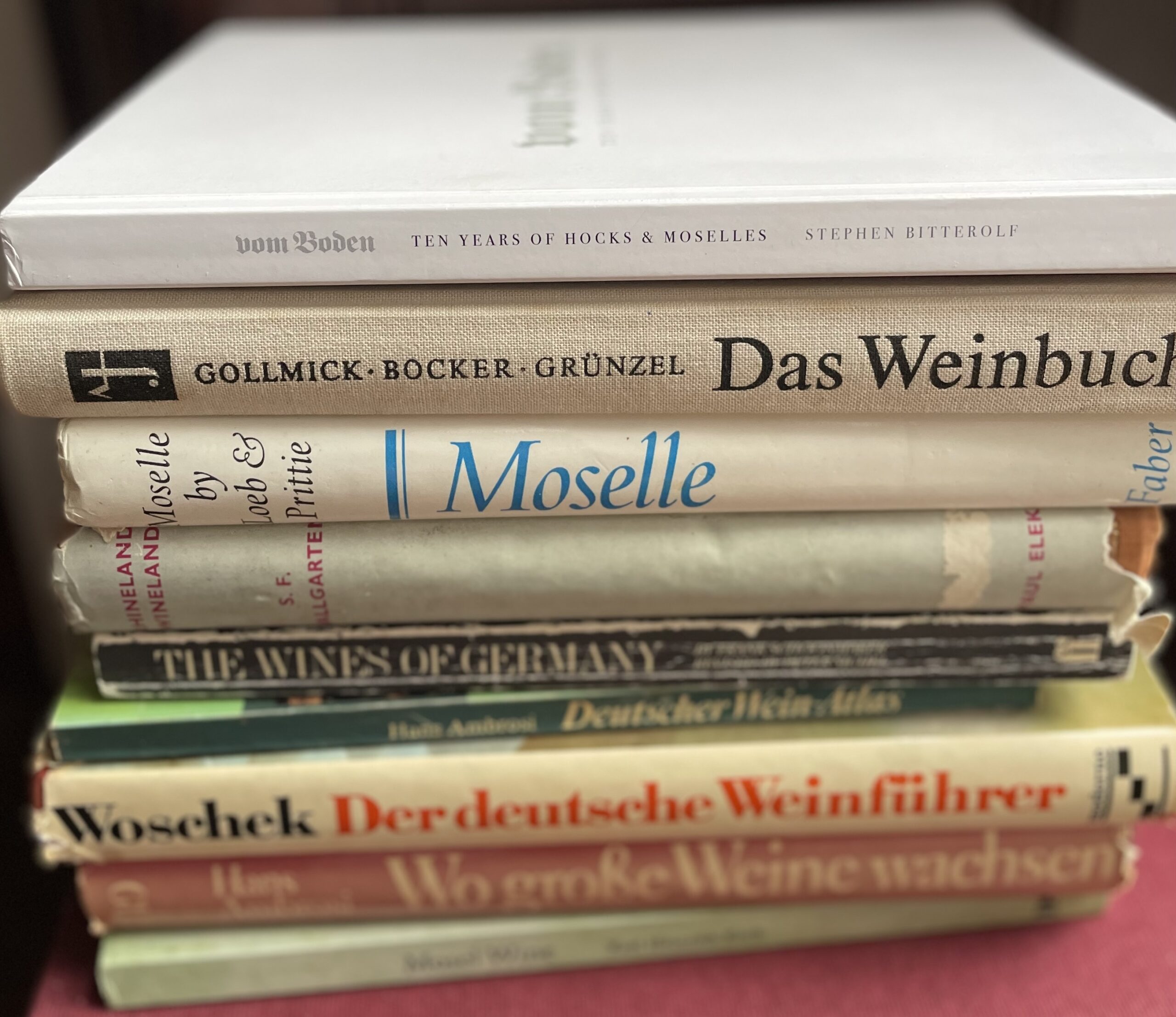

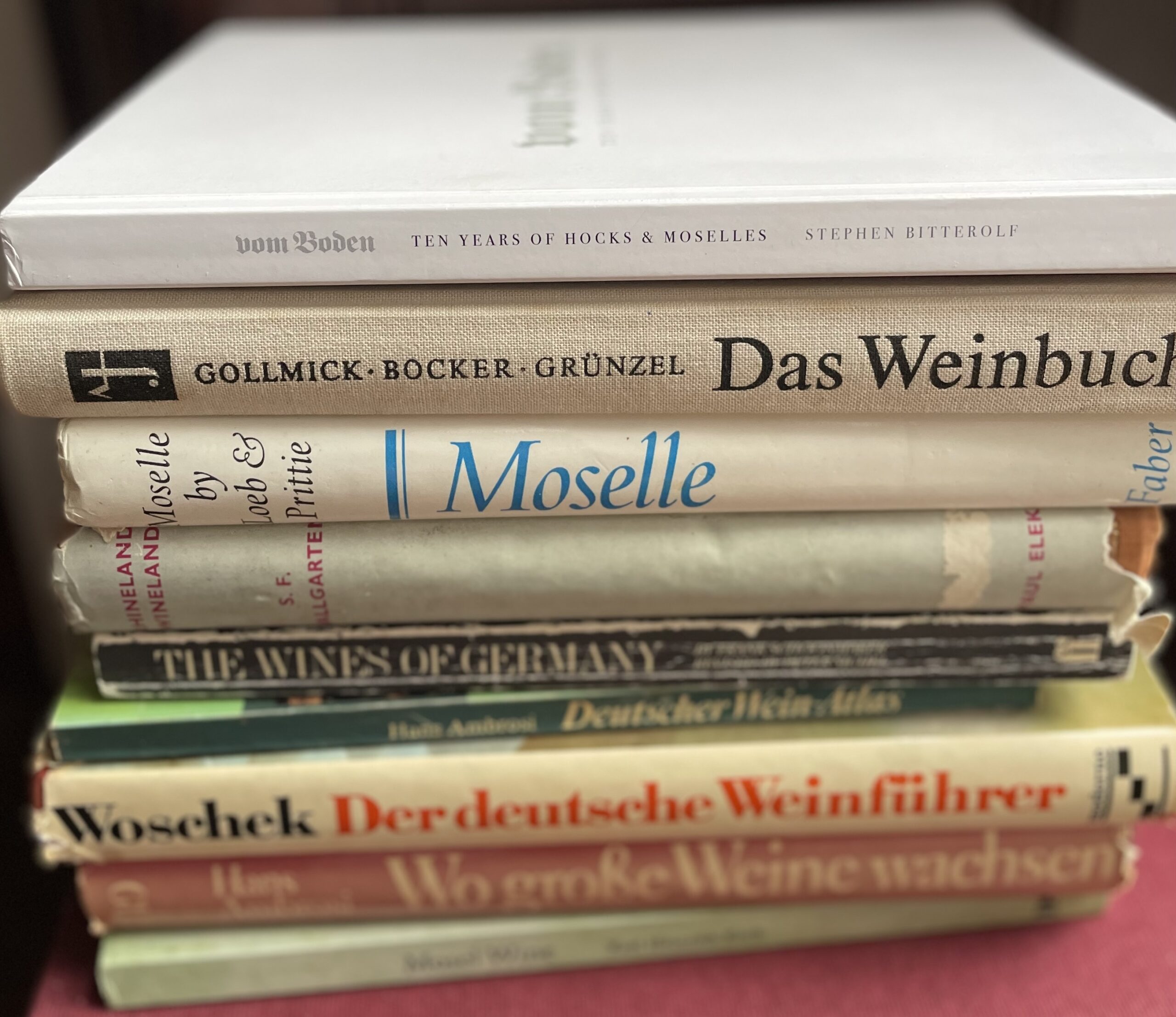

Stephen Bitterolf’s new book “Vom Boden: Ten Years of Hocks & Moselles” in review.

Stephen Bitterolf’s new book “Vom Boden: Ten Years of Hocks & Moselles” in review.

Writer, Editor, Publisher

Valerie Kathawala specializes in the wines of Germany, Austria, South Tyrol, and Switzerland, as well as those closer to her home in New York City. Her work appears in the pages of Noble Rot, Full Pour, SevenFifty Daily, Meininger’s Wine Business International, Pipette, Glug, Pellicle, and a number of other tolerant publications.

It’s an unfortunate paradox: the very climatic conditions that leave us thirsting for lightweight, refreshing and soul-satisfying dry wines render these hard to achieve. Yet, rather than leading the way in surmounting this viticultural challenge, Germany’s Riesling establishment routinely throws up roadblocks. That’s a crying shame. THE CURIOSITY OF “KABINETT” To understand what’s become of “Kabinett trocken,” we must first retrace the steps leading to “Kabinett.” “Cabinet,” as a term applied to German Riesling, dates to 18th-century Rheingau, a derivative of “Cabinetstück” (alternatively, “Kabinet[t]stück”), in use for diverse objects worth displaying in a cabinet of curiosities or, by extension, worthy literary and…...

By Rudolf Trossen The sun recedes, the summer wanes,the ripe grapes long since gifted.A chill arrives under the guise of evening wind,Long shadows stretch heavy like leadacross golden vineyards’ last light. Alone on the slope,I watch in silence. But in old caskschurns young wine,roaring with the summer’s solar might,lust and longing into the night,cheering, laughing, singing bright. I bow beforethe deity’s vigor. November 1994 From the collection Was die Reben Sagen Translated September 2021...

The power, pride and potential of old vines. And it turns out, the Mosel really could be where it all started..

My first true Blaufränkisch moment came in 2013, at a now-shuttered restaurant in Hamburg. Thirty-six bottles from a swath of Austria’s appellations stood open for tasting, from classics like Prieler’s Goldberg 1995 to Marienthal from Ernst Triebaumer to Ried Point from Kolwentz. Those wines impressed me, as they had in the past, even as they failed to inspire me. This time, however, other wines had joined the lineup. The Spitzerberg of Muhr-van der Niepoort (today Weingut Dorli Muhr) , for example; the 2010 Reserve Pfarrgarten from Wachter-Wiesler; and the 2002 Lutzmannsburg Alte Reben from Moric. Suddenly, I was electrified. The wine in the glass was entirely unlike anything I…...

In the first movement of this piece, we looked at the origins of Ludwig van Beethoven’s interest in wine and the critical role this played in shaping the composer’s musical career. Here, we trace his path through Vienna’s living landscape, to find multiple points of intersection between past and present in his music and in some of the city’s defining wines. We then head south to the Austrian spa region of Baden, where Beethoven drank, and composed, masterpieces. As we will find, his music comes more vividly to life when appreciated within the context of the vines and landscapes in which it was written…...

People imagined him to be an alchemist. Granted, it wasn’t gold his slender hands were currently molding, rather a gleaming tinted zinc capsule, encompassing perfect angles and gracing the long slender neck of a curvaceous body. While such language might seem passé in 2021, the characters who regularly participated in such frolics were not. Many were successful, most of them hailing from families older than the states whose passports they’d carry in their bespoke suits. Make no mistake: even here, the wealthier they were, the less attention to proper attire; and don’t let us get started on the unshaven angel…...

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today