Playing Bond, James Bond, at a Swiss Wine Hotel

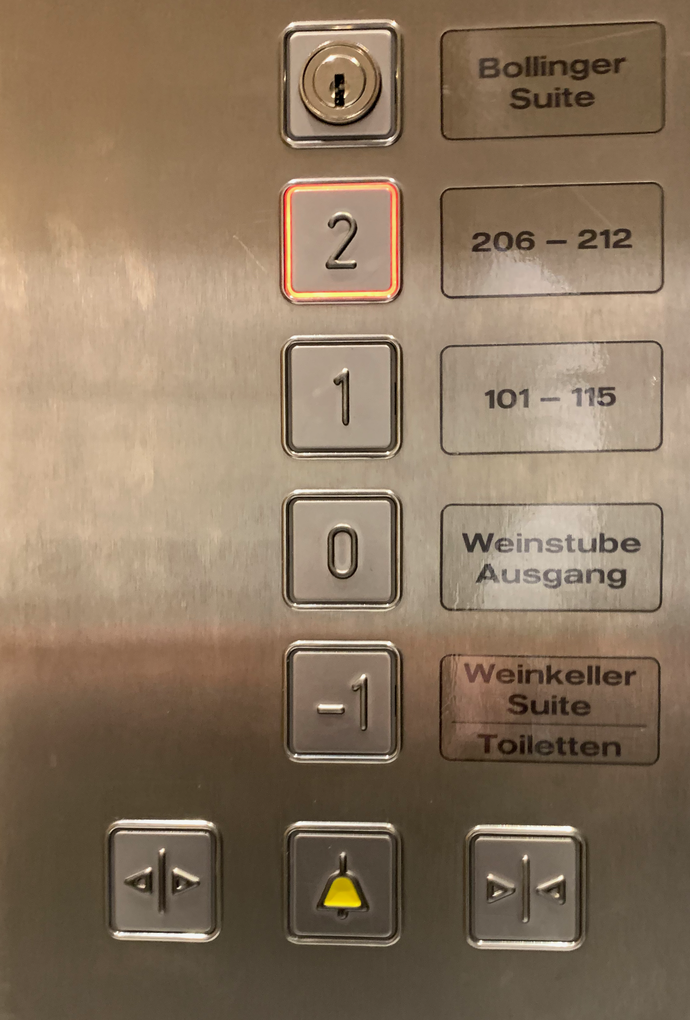

The lure of 007 and having bubbles at their fingertips in the Bollinger Suite pulls some people into Erlinsbach, in northern Switzerland, for a night or two of intrigue. Others fantasize about being lulled to sleep surrounded by gently aging (shhhh) vintage Burgundies in the Wine Cellar Suite. For the rest of us, it’s a simpler dream of a night that opens with great food and a hard-to-find bottle of a Swiss vintage wine. Albi von Felten was ahead of his time when he bought the Landhotel Hirschen from his parents 22 years ago. He and his wife Silvana are gratified to…