Risk and Reward in Austria’s Warming Wachau

In an age defined by climate emergency, can winegrowers in Austria’s warming Wachau react and adapt fast enough to maintain the region’s historic pole position?

In an age defined by climate emergency, can winegrowers in Austria’s warming Wachau react and adapt fast enough to maintain the region’s historic pole position?

Originally trained as a musician, Simon worked variously as a sound engineer, IT consultant and alternative currency designer before wine took over his life. His writing career began in 2011 with the founding of The Morning Claret – an online wine magazine which has become one of the world’s most respected resources for natural, artisanal, organic and biodynamic wine.

His work is published in many print and online publications, including Decanter, World of Fine Wine and Noble Rot. Simon has twice won the Roederer International Wine Writing Award, most recently for his first book, Amber Revolution: How the World Learned to Love Orange Wine, published in 2018 and since translated into five languages. His second book, Foot Trodden, is a collaboration with author and photographer Ryan Opaz and celebrates artisanal winemaking in Portugal.

Simon is also active as a wine judge, translator and editor. He is a keen cook and lover of music ranging from Stockhausen to ClownC0re. He lives in Amsterdam with his partner Elisabeth.

Pinot Blanc is neither a distinctive cépage nor a particular grape variety – at least, not from the viewpoint of ampelography or genetics. And what there is of pure Pinot Blanc worldwide is nearly all rendered in German-speaking growing regions where it is typically known as Weissburgunder.

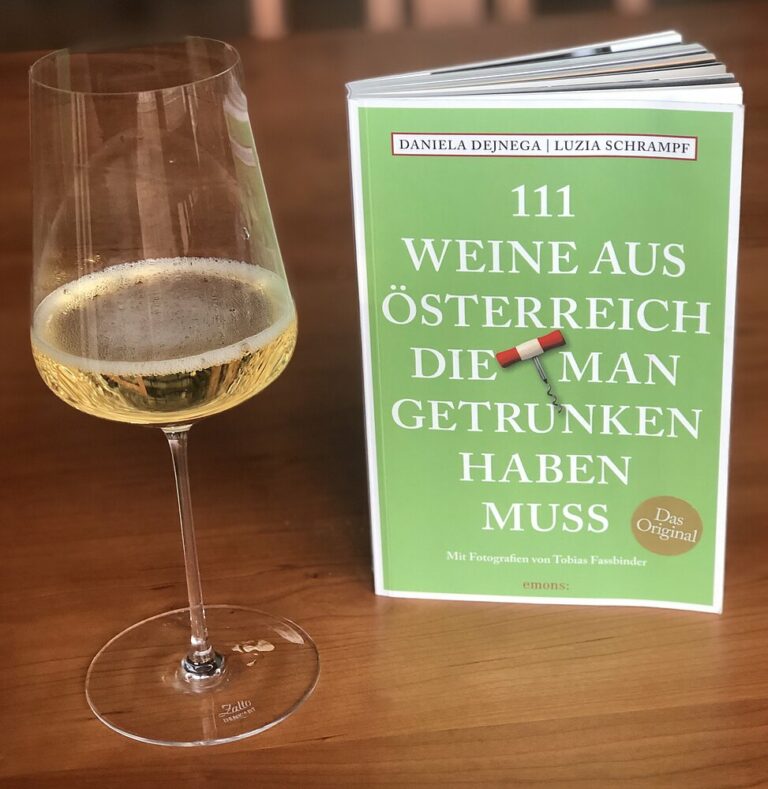

Austrian sparkling wines are filled with adventure, from serious Winzersekt (Austria’s answer to grower Champagne) to the refreshing fizz of pét-nat, a style the country was quick to embrace. The adoption of a three-tiered quality pyramid for Austrian sparkling wine in 2015 helped set the stage. The book 111 Austrian Wines You Must Not Miss includes nine sparkling wines that illustrate this effervescent trend. Three I’d like to spotlight here are the outstanding Winzersekte of Ebner-Ebenauer and Fred Loimer, which represent the absolute pinnacle of quality, as well as a pét-nat that was one of the first to make a splash…...

Austrian wine splashed back into the headlines recently when four of its wineries were chosen by a leading U.S. wine publication for inclusion in their “Top 100” worldwide. Notably, three of the four made their names with red wines. What’s more — in a first for Austria — one is a woman. The woman in question, Dorli Muhr, has been a powerful catalyst for the rise of Austrian wine over the past three decades. But gaining international recognition for her own wines, particularly her strikingly finessed Blaufränkisch from a vineyard she was the first to champion, has been a long…...

Is there a way to understand a vineyard? Wines from certain sites evoke the urge to uncover more about the place and the reason the wines taste the way they do. These are wines that, whatever the vintage or producer, manage to stay true to some sensory basics. Riesling might be the medium, but the message is origin. Geography and geology are where the notion of terroir begins. To understand a vineyard is to listen to what place tells us through location, aspect, and soil. Zöbinger Heiligenstein in Kamptal, Austria has plenty to say. The brave little vineyard: Heiligenstein’s storied…...

Channeling literary theory in order to propose a new threshold test for fine wine.

This article is an excerpted chapter from We Don’t Want Any Crap in Our Wine (2019). After the book went to print, the Rennersistas informed the author that Susanne Renner left the winery, which will now be run by siblings Stefanie and Georg. In 2015, Susanne and Stefanie Renner took over the family wine business in Gols, Austria and became their parents’ bosses. In short order, the sisters converted to biodynamics and created their own line of wines, Rennersistas, in addition to the family’s traditional red Renner cuvées. Ever since, Susanne and Stefanie have reveled in the freedom of making…...

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today