What’s the Point of Fine Wine, Afterall?

Channeling literary theory in order to propose a new threshold test for fine wine.

Channeling literary theory in order to propose a new threshold test for fine wine.

Writer, Editor, Publisher

Paula Redes Sidore moves smoothly between the worlds of wine and words. In 2012, she founded Weinstory, a creative content and translation agency dedicated to transposing the world of German-speaking wine into English. TRINK is the natural extension of that pursuit. She is the German and Austrian regional specialist for jancisrobinson.com and a member of the Circle of Wine Writers. Paula has a Masters degree in fiction writing, and her work has been featured in jr.com, Sevenfifty Daily, Feinschmecker, and Heated. She lives on the northern wall of wine growing with her family in Bonn, Germany.

We British are not the world’s most noted linguists, but that doesn’t seem to put off some of us from drinking “German-speaking” wines. That said, the market for these wines has had a rough ride at times, which makes their current increasing popularity all the more intriguing. Germany has historically boasted a well-established presence in the U.K. wine market. In the 19th– and early 20th– centuries German wines were famously on par with Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, and Port in terms of price. After the fall of Napoleon, the Rhineland and the Mosel both entered a period of prosperity, initiated by…...

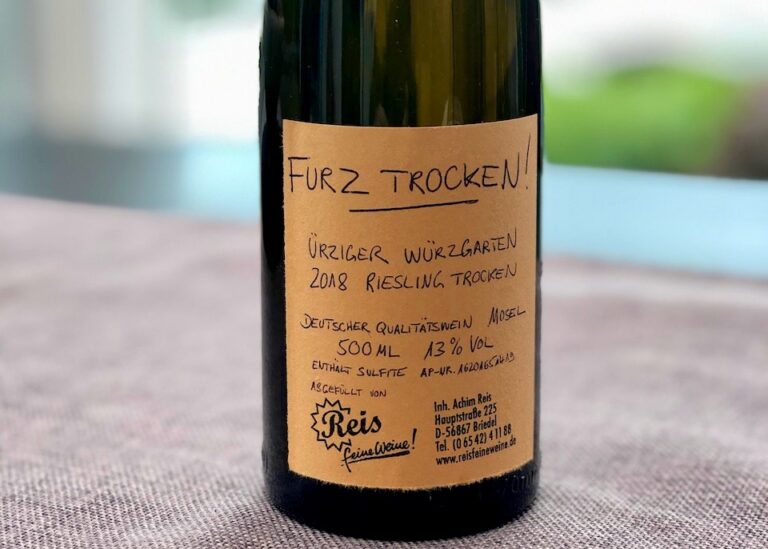

The dark wit of Berlin. Dangerously low water levels in the Rhine River. Black bread. Germany does trocken like few others. And then there’s the wine. Despite its reputation as the land of Blue Nun, more than 60 percent of the wines made in Germany are dry. And within that 60 percent, there are discernible levels of dry, drier, and driest. So dry, in fact, that there’s a strangely specific word for it. (Of course there’s a word. It’s Germany. There’s always a word.) Furztrocken. Fart Dry. Literally. As difficult to grasp as I find a term like feinherb, it’s Kinderspiel when compared to furztrocken. Then again, mindset…...

I reach down to the baggage carousel and slip the strap over my shoulder, the weight of a month’s traveling slowly spreading through my frame, equalizing itself. I pause. Something feels wrong. There is a dampness between my shoulder blades and a smell that doesn’t belong: windfall cherries, woodsmoke. I look down to see a small, red pool forming behind my heels. A man in a yellow jacket reaches for a walkie-talkie. The source is a now-leaking bottle of Fritz Wieninger’s Pinot Noir Select 2006, naively swaddled in pair-upon-pair of walking socks. It’s a memento of one of those evenings…...

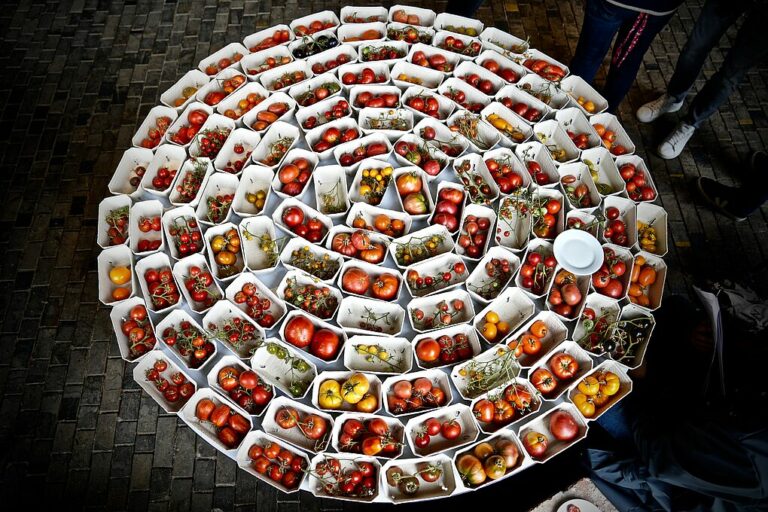

Calling from the expansive, flat landscape that forms the western edge of the Pannonian Puszta steppe flatlands, Erich Stekovics is a lone voice in the tomato world. Where others seek high yield and hardy reliability, Stekovics makes the case for flavor and site. He and his wife Priska belong to the tiny share of Austrian farmers cultivating tomatoes without the cover of glass or foil, and without irrigation. At the eponymous estate in Frauenkirchen, the pair cultivate and safeguard several thousand varieties in the open, and in addition to chili peppers, onions, and garlic, their fields are surrounded by vines…....

Sekt embodies free spirit, hedonism, even — in its blatant disregard for rules — punk. The limitless maximization of lust for life and the unadulterated joy of the sensual assume the spotlight, while ethics and morals are asked to exit stage left. Whether it’s to christen a ship, toast a victory, or celebrate a birthday in the office (back when we did things like this), bubbles embrace the sparkling side of everyday life. A flash of glam on an otherwise wretched Tuesday afternoon. Sekt is bound to nothing and to no one, neither to food nor occasion. And that’s why…...

Two wine luminaries reflect on the complex and challenging process of taking Austrian vineyard classification from bill to law.

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today