Journey to the Center of the Mosel: a Nordic Perspective

How a former chef’s trip from the Norwegian Fjords to Germany’s Mosel valley took wine appreciation to the next level.

How a former chef’s trip from the Norwegian Fjords to Germany’s Mosel valley took wine appreciation to the next level.

Håvard Flatland is a chef and freelance wine writer. He enjoys wine from many angles, from the conviviality of bottles and friends to scrutinizing the tannic structure of a Barolo. For three years he worked as sommelier at Park Hotel Vossevangen and he once came second in a national cake competition.

This is a story for the wine romantics among us who dream of bygone varieties, who hunker down to listen to the old stone terraces telling stories of yesteryear, of those with a weak spot for growers and wines committed to character. It is in this world of nostalgia and nerds that this story is set. Enter Ulrich “Uli” Martin, a viticulturist from Gundheim in Rheinhessen. “Such a reliable companion!” he says. “Honest, direct, and amiable. You sense it immediately.” This high praise, however, is not aimed at his best friend, at least not in the traditional sense. Rather, at a grape…...

Why does biodynamics matter? Respekt-BIODYN is the ongoing effort of 25 growers from German-speaking wine regions to answer that question. Though there are many forms of holistic farming that benefit people, planet, vines and wines, this tight-knit Austria-based group believes that a shared commitment to viewing the teachings of philosopher and agricultural reformer Rudolf Steiner as a springboard for exchange, cooperation, shared learning, and support helps cultivate a sense of individuality that, ultimately, translates into more profound terroir expression and higher quality in their wines. Biodynamic Origins “The first 12 winemakers started in 2005,” explains the group’s leader, Michael Goëss-Enzenberg…...

10 sparkling secrets of the sekt generation.

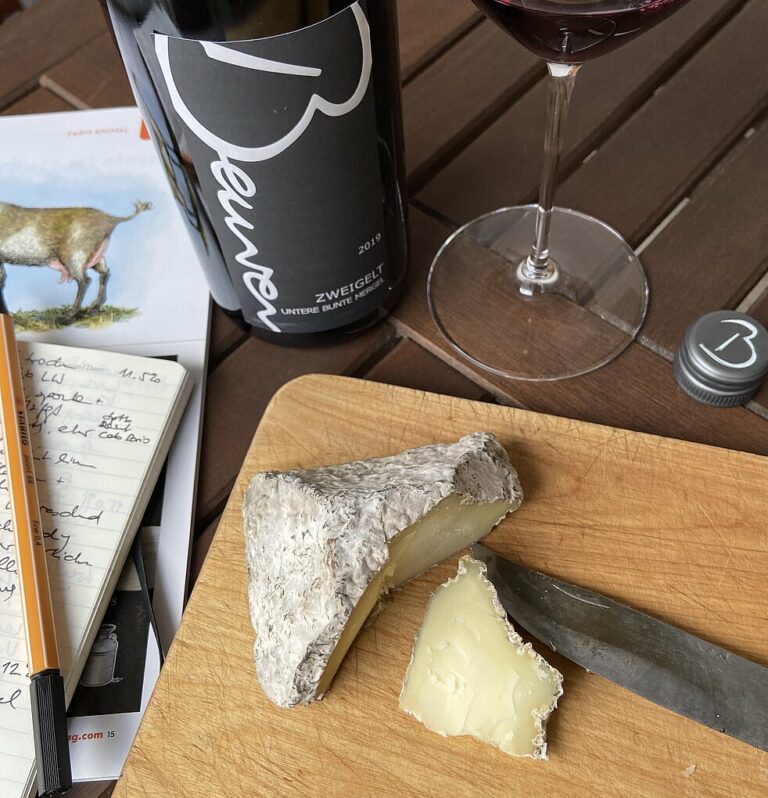

When Westphalia and Württemberg meet on the table good tastes are bound to happen.

March 25, 2024 Update: Schmetterling has closed. It’s owners hope to reopen in the future. Are there parallels between German and Austrian wines, small-scale farming, and the queer community? If so, the most essential may be a shared need for safe space. Schmetterling, a queer-forward natural wine and vinyl shop that opened this summer in rural Vermont, aims to offer just that. By prioritizing the needs of communities at — admittedly starkly unequal — risk, owners Danielle Pattavina and Erika Dunyak have created an unlikely outpost for low-intervention German, Austrian, and other Alpine wines. The shop is both an incubator…...

Can German Pinot Noir finally catch on or is forever fashionably spät(burgunder)?

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today