A Remembrance of German Wines Past

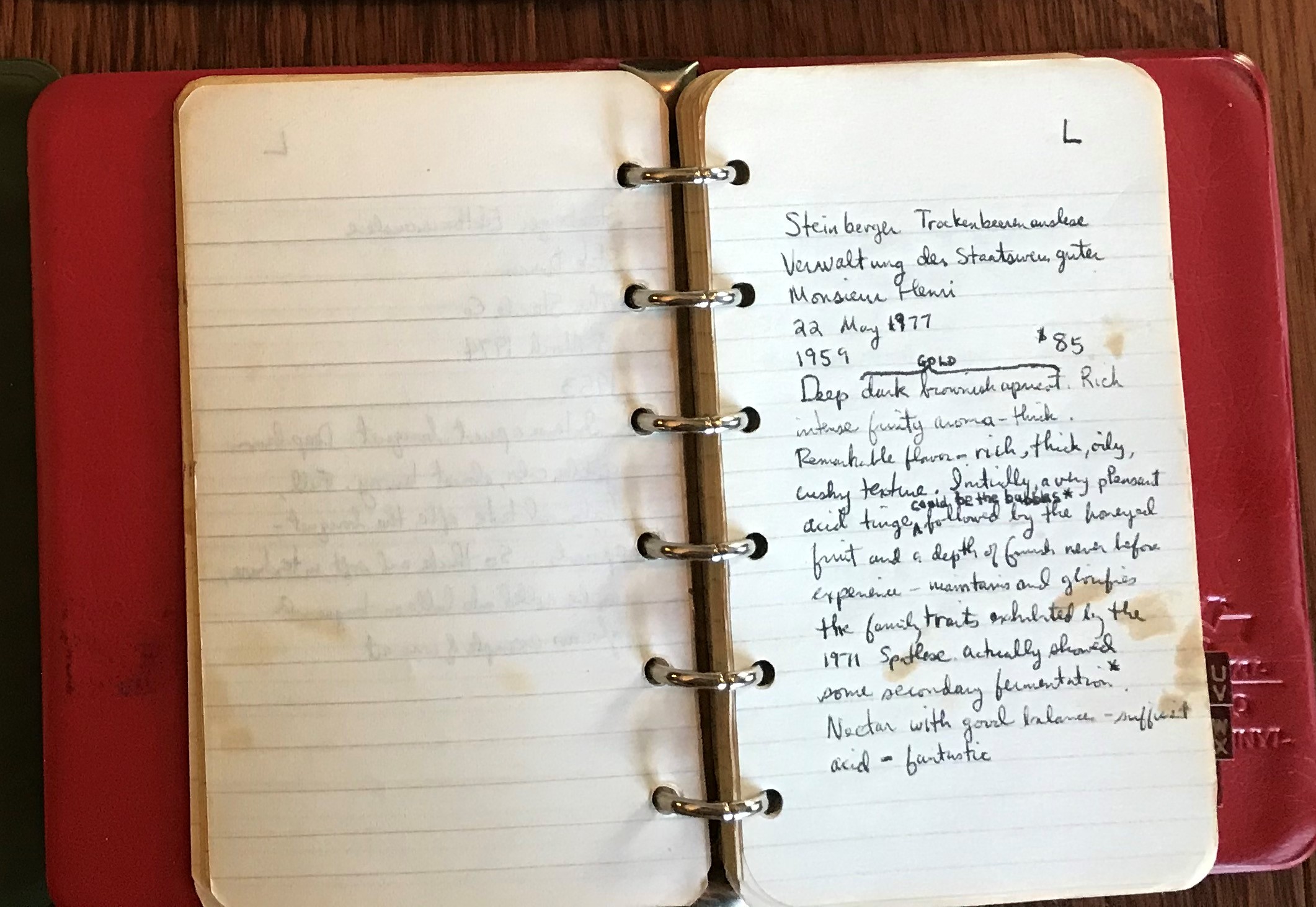

My twenty-something self left two gifts for the older man I would become: a doctorate in applied mathematics and four small, looseleaf notebooks. The degree opened many doors and reinforced my ability to do independent research, perform analyses, and document the results. The notebooks, along with labels from many of the bottles, form an archive of my first decade tasting wine. Between 1969 and 1979, a period covering my student and early career years, I kept detailed notes on almost everything I tasted. During most of that time, I lived in Evanston, Illinois. It was dry until 1975, necessitating runs…