Releasing the Power of Hidden Sweetness

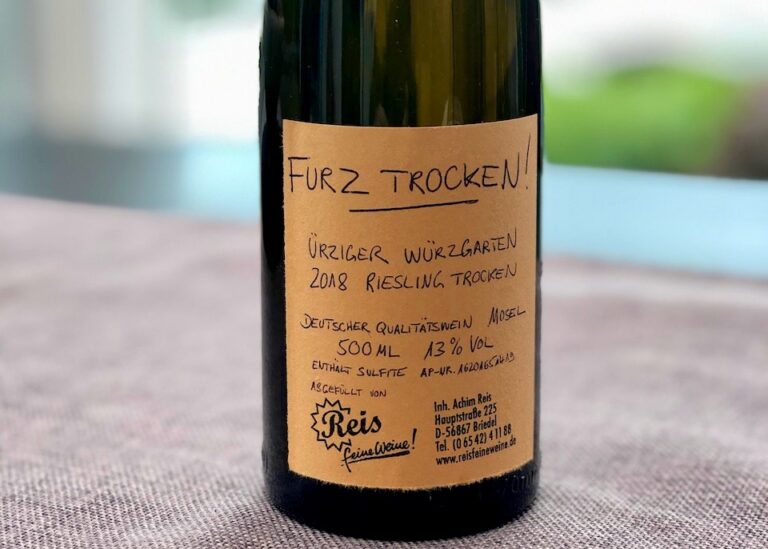

“Dry” describes what wine drinkers overwhelmingly profess to desire. And “trocken” can only appear on labels of German Rieslings with less than 10 grams of residual sugar. If one desires sweetness, there is no lack: Most of today’s Kabinetts are higher in sugar than were Auslesen of the 1980s. (Granted, the grapes were probably also higher in must weight.) Aesthetically as well as commercially, success in the realm of legal dryness—Trockenheit—as well as that of pronounced sweetness, can scarcely be denied. German Riesling growers have long since succeeded in proving that they too can render world-class dry wine, while simultaneously…