Better Spät than Never in the Ahr

How catastrophe proved a catalyst for change, and helped Germany’s Pinot paradise find a new way to farm.

How catastrophe proved a catalyst for change, and helped Germany’s Pinot paradise find a new way to farm.

Originally trained as a musician, Simon worked variously as a sound engineer, IT consultant and alternative currency designer before wine took over his life. His writing career began in 2011 with the founding of The Morning Claret – an online wine magazine which has become one of the world’s most respected resources for natural, artisanal, organic and biodynamic wine.

His work is published in many print and online publications, including Decanter, World of Fine Wine and Noble Rot. Simon has twice won the Roederer International Wine Writing Award, most recently for his first book, Amber Revolution: How the World Learned to Love Orange Wine, published in 2018 and since translated into five languages. His second book, Foot Trodden, is a collaboration with author and photographer Ryan Opaz and celebrates artisanal winemaking in Portugal.

Simon is also active as a wine judge, translator and editor. He is a keen cook and lover of music ranging from Stockhausen to ClownC0re. He lives in Amsterdam with his partner Elisabeth.

The intimate wine bar from Holger Schwedler, the size of a Texas walk-in closet, sat off a quiet pedestrian alley not far from the famous curative hot spring of Wiesbaden, the Kochbrunnen. Too small for a kitchen, the wine bar encouraged patrons to bring their own vittles, which, like the guests, included a variety...

What do one of the Mosel’s oldest winemaking estates and a country with a fledgling wine-drinking culture have in common? The answer, as with most things in life, is Riesling. “German Riesling has become a synonym for white wine in Finland,”” says Heidi Mäkinen MW, Portfolio Manager for Viinitie Oy, one of that country’s largest importers of German wine. “Finns like the freshness and fruit, and Riesling is one of those wine words that’s incredibly easy to pronounce.” As Viinitie’s new portfolio manager, Mäkinen, for whom work and private life has little separation, has kicked off her holidays 2,000 kilometers south of her…...

Home is where the vines grow. We’ve all heard variations on that theme. But just how far can that idea be taken? Wein Goutte offers one answer. This portable micro-estate — whose first vintage sold out in a blink — is the brainchild of husband-and-wife team Christoph Müller and Emily Campeau. The concept goes beyond negociant but stops well short of flying winemaker. And it presents an entirely new model for a footloose generation’s interpretation of the relationship between vintner and site. Campeau, a fierce lover of food and wine (and a vivid writer on both), is originally from Québec. Her experiences…...

Channeling literary theory in order to propose a new threshold test for fine wine.

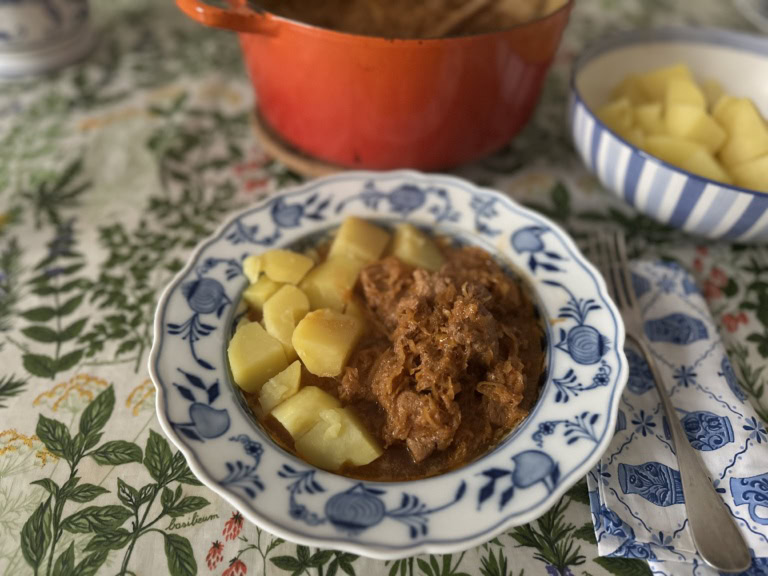

Luisa Weiss's recipe (and pairing) for a heartwarming bowl of gulasch and Gemütlichkeit in Germany's capital city.

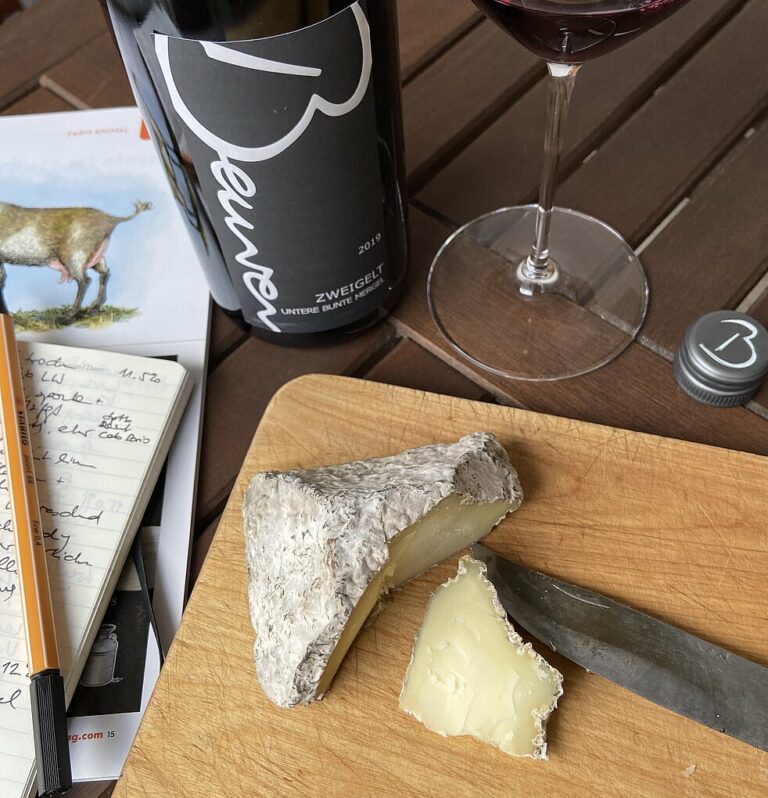

When Westphalia and Württemberg meet on the table good tastes are bound to happen.

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today