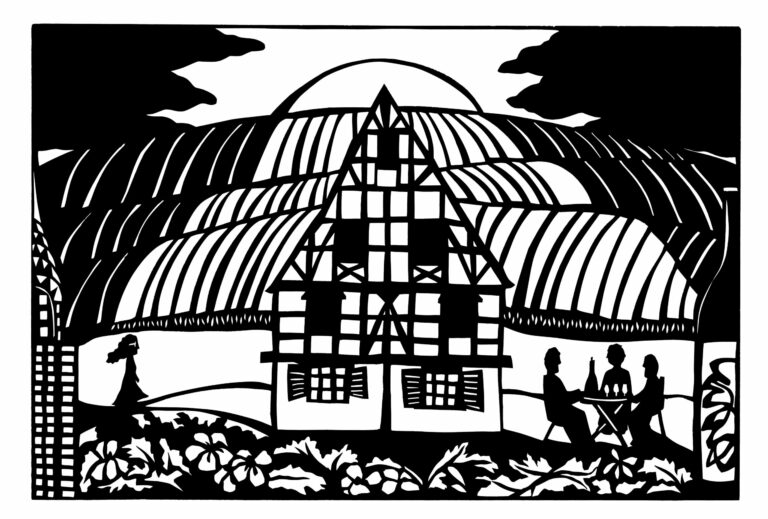

But for that Umlaut

The spelling of grape names can be fraught. Iconic viticulturalist Georg Scheu once delivered an address, accompanied by a poem, wittily satirizing those who would replace Sylvaner’s romance “y” with “i.” In 1940, that was risky. Scheu’s country had become a terror state, and those being spoofed weren’t known for their sense of humor. Pfalz vintner Rainer Lingenfelder long labeled his Sylvaner: “Ypsilon – Homage to Georg Scheu and his Rebellion against the ‘i’-dot Bureaucrats [i-Punkt Bürokraten]” — which gained hilarity in translation given the fatuous Nazi policy of enforcing “Germanic” spelling. (Even the “c”s in Cabinet and Bernkasteler Doctor…