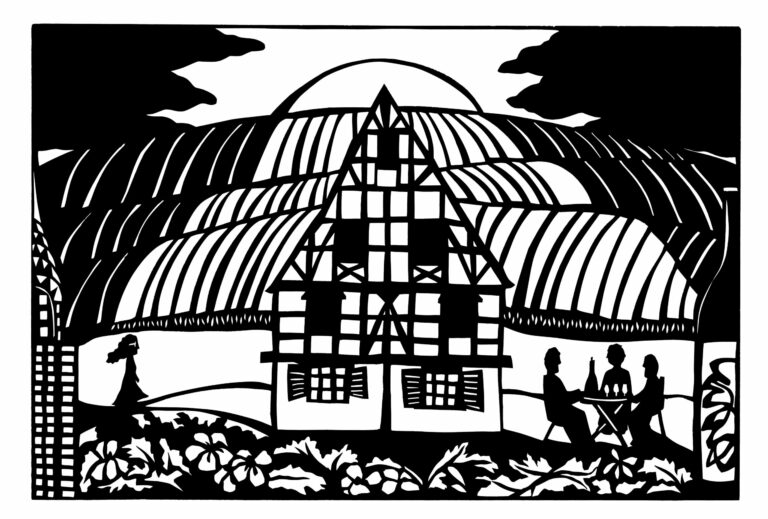

In Alsace

The ancient injunction to keep your friends close and your enemies closer is all very well, but in Alsace it can be hard to tell the two apart. Control of the region has swung between Germany and France like a pendulum, and the Protestantism of the one and Catholicism of the other has caused generations of religious dissidents to flee west and east respectively, to halt by the great Vosges mountains and settle on the swathe of land beside the Rhine. Which, it turned out, might have been a problematic spot in political terms, but was an ideal place to…