Ingelheim: The Spätburgunder Hotspot You’ve Never Heard of

Ingelheim Rheinhessen is a hotspot for German Pinot Noir (Spätburgunder).

Ingelheim Rheinhessen is a hotspot for German Pinot Noir (Spätburgunder).

Kevin Puls works in advertising and PR. His passion for Austrian wine began nearly two decades ago and he's regularly tasted the vintages of the Alpenrepublik from the Wachau to Styria. His weakness for estates that work organically and for natural wines started with Gut Oggau's 2007 vintage. He's also a regular visitor to Franken. He blogs about food, wine, and the people who make them.

A handful of Weinheim visionaries are reshaping the future of German wine in the country's largest winegrowing region with lessons from the past.

Curing fish is a bit like baking cakes: unless one follows a particular recipe to the letter, the final result inevitably contains an element or three of surprise. Once in the oven, once in the brine, the window for intervention has passed – leaving time and temperature as the only remaining levers. I clearly lack the discipline to work with exact measurements (thus explaining my ban from baking birthday cakes), but I do enjoy the imprecise, historical art of preserving food with salt. Think: classic Sauerkraut, southern German Surfleisch, or – well – salmon. This particular side of freshly caught salmon…...

A jack of all trades is inherently a master of none. While finding the right focus can help, that is often easier said than done. Sometimes a more drastic solution is needed. Intervention, anyone? Rheinhessen! I’m so glad you could make it today. Won’t you join us? Feel free to grab something to eat before you sit. There’s coffee, tea, and water. And a big box of tissues, in case we need those later. Wine? No, at least not like that. But I’m glad you raise the issue, because wine is actually what’s brought us together here. I know this won’t be…...

This is a story for the wine romantics among us who dream of bygone varieties, who hunker down to listen to the old stone terraces telling stories of yesteryear, of those with a weak spot for growers and wines committed to character. It is in this world of nostalgia and nerds that this story is set. Enter Ulrich “Uli” Martin, a viticulturist from Gundheim in Rheinhessen. “Such a reliable companion!” he says. “Honest, direct, and amiable. You sense it immediately.” This high praise, however, is not aimed at his best friend, at least not in the traditional sense. Rather, at a grape…...

For over a year, we’ve been living with a pandemic that has shut down more than just our senses of taste and smell. It has forced us to rely on at-home experiences like a glass of wine to satisfy our longing for travel. But what do the places of our terroir dreams taste like? What exactly constitutes the origins of a wine? To use a loaded German word, how much Heimat (loosely, homeland) is in terroir? Flash back to harvest 2012. Max von Kunow of Weingut von Hövel in Germany’s Saar visits the Jurtschitsch family in Austria’s Kamptal for a vacation before his own harvest. Together…...

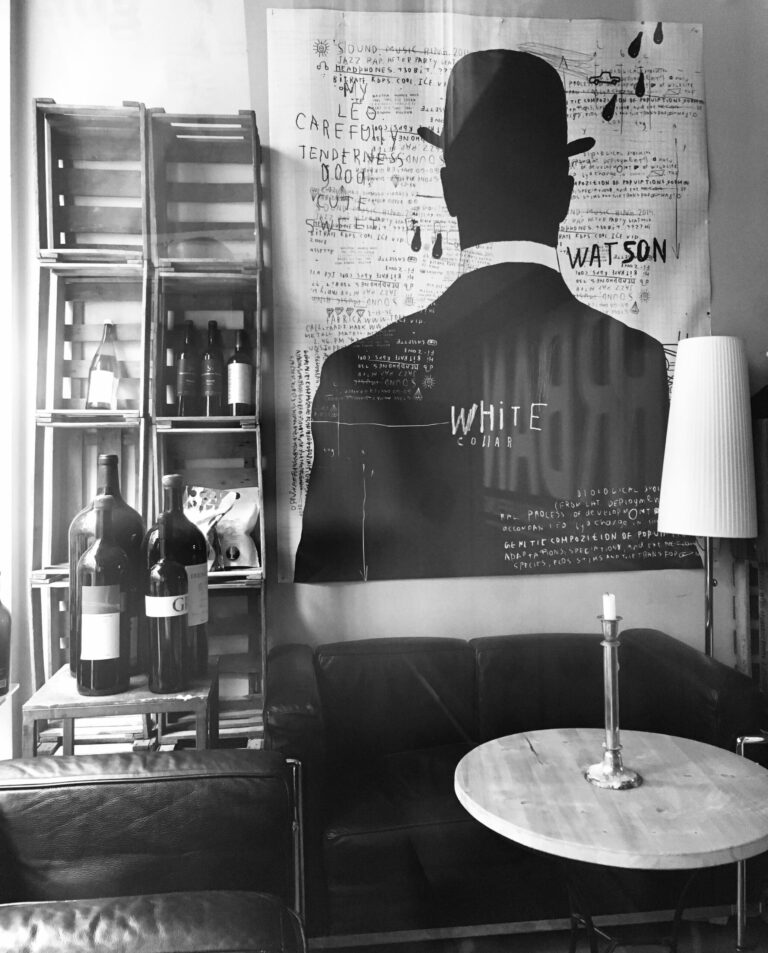

The intimate wine bar from Holger Schwedler, the size of a Texas walk-in closet, sat off a quiet pedestrian alley not far from the famous curative hot spring of Wiesbaden, the Kochbrunnen. Too small for a kitchen, the wine bar encouraged patrons to bring their own vittles, which, like the guests, included a variety...

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today