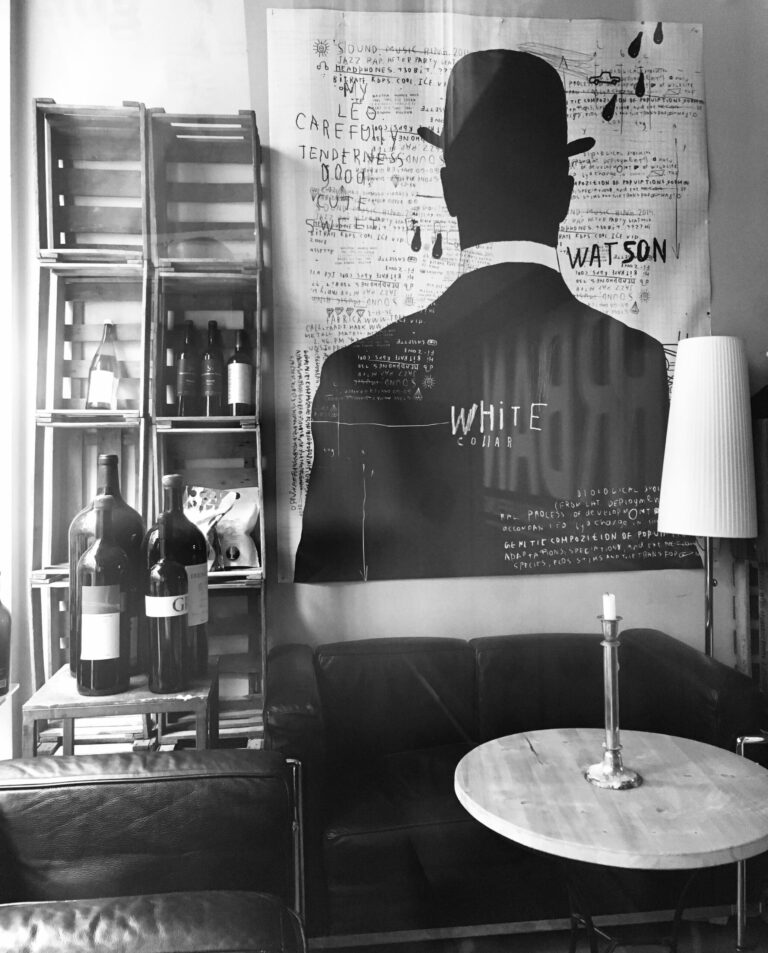

Something Red

The wine stood on a high shelf, past tense very much called for, because moments after the waitress leapt for it — leapt, did not get a stool, did not ask for help, leapt because she once could — the bottle wobbled and began to fall. On earth, objects plummet at a pace of 9.8 meters per second squared, which means this bottle will reach the ground approximately two-thirds of a second after it begins its journey. But as any oenophile knows, wine makes a moment last — in this case, long enough to share exactly 15 things about this…