Wine at the 51st Parallel in Saale-Unstrut

Trink Magazine | That viticulture is still possible in Germany’s Saale-Unstrut in an age of climate crisis is due to the microclimate of the valleys and the perseverance of its growers.

Trink Magazine | That viticulture is still possible in Germany’s Saale-Unstrut in an age of climate crisis is due to the microclimate of the valleys and the perseverance of its growers.

Christoph Raffelt is one of an exciting new vanguard of voices when it comes to German wine. And voices is not a euphemism here, as it is indeed his voice together with his stellar cast of winemakers and guests that come together on his monthly podcast Originalverkorkt.de; while his words appear in his online magazine of the same name. He's been on the road since 2016 with Büro für Wein & Kommunikation as a freelance journalist, copywriter and all-round wordsmith. His work has appeared in such esteemed publications as Meiningers, Weinwirtschaft, Weinwelt, Sommelier, Champagne-Magazin and Schluck.

We’ll come right out and say it: Franken (Franconia) is Germany’s most underrated region. If you still think of it as the source of wan wines poured from squat flagons and drunk mostly at home, we’re here to let you in on a secret: there has never been a more exciting time for this corner of northern Bavaria, where wine, not beer, rules the day. The region sits just below the 50th parallel and at the cool, eastern edge of Germany’s wine core. It’s a perilous position for viticulture. As decades of frost-crimped and extreme-heat-affected vintages attest, its starkly continental…...

The photos that German astronaut Alexander Gerst sent back from the International Space Station during summer 2018 were deeply shocking: Germany was no longer green, but brown. The only visible green in the entirety of many of the wine regions was in fact the vines. RIP cool climate? While it was common knowledge that the summer of 2018 had been exceptionally warm, few people realize it was also the warmest ever recorded. The Average Growing Season Temperature (AVGST) registered at Geisenheim/Rheingau in 2018 was 17.8° Celsius, or 0.9° (1.6° on the Fahrenheit scale) above the previous record year, 1947. However, most were…...

I’ve been a fan of B sides since, well, pretty much since there have been B sides. Record companies have historically used vinyl’s flipside as a holding pen for unreleased or less desirable concept material. Pieces that don’t fit the brand; supplementary songs with minimal hopes and lower aspirations. Filler. Yet, to me B sides embody the edgy and unpredictable, the vulnerable creative underbelly of both artist and medium. Let’s call rosé, the pink “wunder” of the last decade, our A side. Industry figures show that rosé now constitutes some 9% of the global wine market. Thirty-nine percent of wine drinkers in…...

Franken was slower to wake up the wine counter culture revolution in Germany, but young growers are now more than making up for lost time.

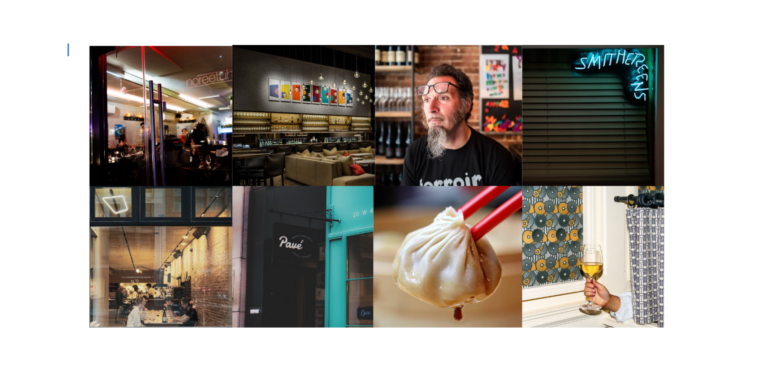

Whether you’re dropping into town for the bacchanalia that is Rieslingfeier or you’re a native New Yorker curious to get a taste of the latest and greatest in German and Austrian wines, here’s your hit list of bars and restaurants that make NYC the country’s best (if priciest) city to drink auf Deutsch. G = German focus A = Austrian focus Noreetuh (G) Manager and co-owner Jin Ahn has turned this decade-old Lower East Side Hawaiian spot into the city’s ultimate insider Riesling hangout. Ahn’s exceptionally well-informed list is divided into Rieslings “25 years of age or older” and “younger than…...

“Free your mind and the rest will follow.” Coming from one of the co-owners of Germany’s oldest wine trading houses, one might suspect a quote from Goethe, Schiller, or Nietzsche. It’s actually the American R&B/pop group, En Vogue. And that makes for a jarring, if fitting, introduction to my conversation with these stewards of tradition in German wine that look back to 1786 in Worms as easily as they look ahead to 2019 Organic Madonna. P.J. Valckenberg has the history and the pedigree, no question. Its customers have included the Swedish royal family and Charles Dickens. In addition to a truly impressive portfolio…...

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today