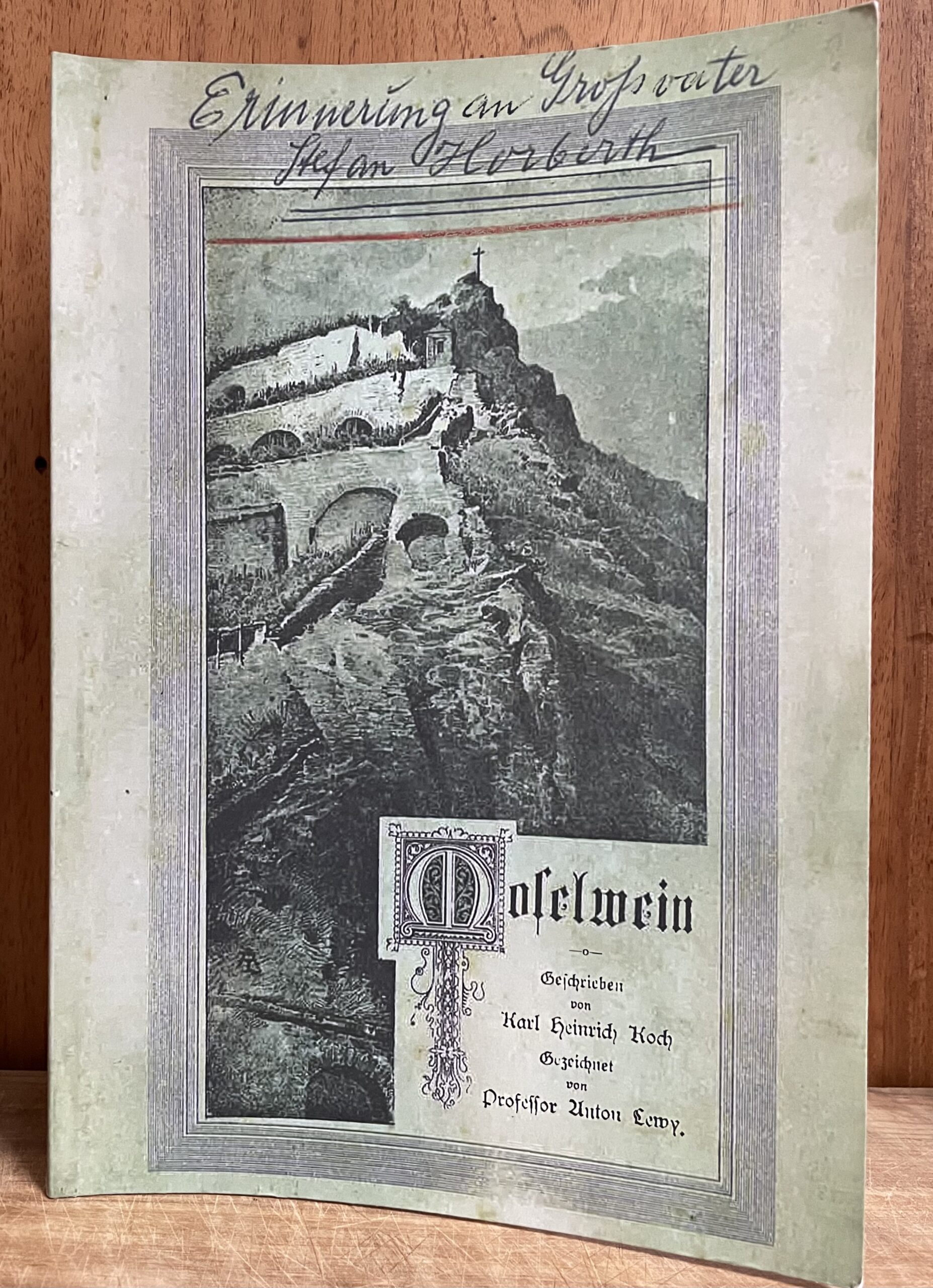

Book Review: “Mosel Wine”

We like to think of Mosel wine as eternally glorious. The river valley’s nearly 2,000-year vinous history, its relics of Roman civilization and tributes to Celtic wine gods, its very viticulture carved with seeming permanence into stony banks all suggest an unbroken line. But an excellent new book, edited by Lars Carlberg, with able assistance from David Schildknecht, Kevin Goldberg, and Per Linder, underscores the extent to which the Mosel’s glory has been far more ebb than flow. Such awareness only makes the late 19th-century golden age that is the book’s focus more luminous. The book nests together several components….