Quo Vadis, Alto Adige?

Südtirol-Alto Adige winegrowing has already exerted tremendous energy in re-inventing itself. But as has become ever clearer, that was only step one. The second is yet to come.

Südtirol-Alto Adige winegrowing has already exerted tremendous energy in re-inventing itself. But as has become ever clearer, that was only step one. The second is yet to come.

Christoph Raffelt is one of an exciting new vanguard of voices when it comes to German wine. And voices is not a euphemism here, as it is indeed his voice together with his stellar cast of winemakers and guests that come together on his monthly podcast Originalverkorkt.de; while his words appear in his online magazine of the same name. He's been on the road since 2016 with Büro für Wein & Kommunikation as a freelance journalist, copywriter and all-round wordsmith. His work has appeared in such esteemed publications as Meiningers, Weinwirtschaft, Weinwelt, Sommelier, Champagne-Magazin and Schluck.

Lunar New Year (aka Spring Festival, or Guo Nian in Mandarin) is arguably the most important holiday for people of Chinese heritage — especially in Taiwan, where I grew up. It’s been my favorite since I was a kid. Now, living in Brooklyn, I recall that a few days before the New Year every household starts to “sweep the dust” to banish bad luck, erase unhelpful habits, and create positive new ones. On the day before New Year’s Eve (a holiday we call Little New Year’s Eve), we will take down the old Spring Festival couplets and replace them with fresh verses. On New…...

Pinot Noir from Switzerland? Gantenbein! Donatsch! Hardly another country exists whose reputation among international wine lovers for producing quality wines from this variety boils down to just two names. It’s high time that other Swiss producers get some of that spotlight – and there’s no reason why they shouldn’t come from the Canton of Zürich. Deutschschweiz, the sizable swath of eastern Switzerland that is German-speaking, is Pinot Noir land. Reportedly, the vine was introduced to Graubünden in 1631 by the Duke of Rohan, as a gift to local farmers, to win them over as mercenaries during the 30 Years War…....

The Alto Adige winemaker orchestrating a symphony of terroir-driven wines that transcend borders and time.

It starts with the soil. “I am passionate about the microbial world under our feet, and the key role it plays in the vine’s adaptation to climate change,” says agronomist Martina Broggio, a sustainable viticulture consultant in northern Italy, Tuscany, Marche, and Puglia. Since 2018, Broggio has been helping wineries in Alto Adige move in a regenerative direction. Regenerative Viticulture (RV) requires a significant paradigm shift within vineyard management, where soil is understood as a living environment rather than as a container for growing grapes. It envisions an ecosystem in which all parts of the vineyard, including roots and bacteria,…...

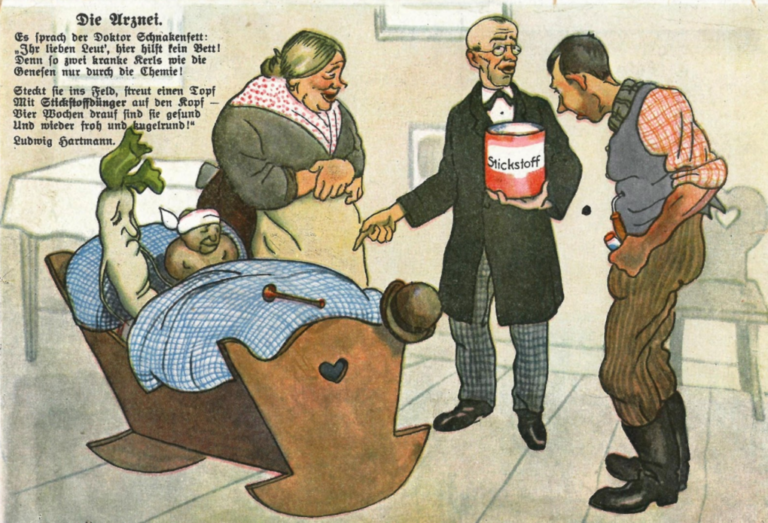

Above, a postcard from the German fertilizer industry of the 1920s. At the time, perspectives on soil were changing: Until then, people had spoken of plant growth as being affected by forces; afterward, it was substances. Deficiencies could simply be addressed with the help of agrochemistry. As recently as a decade ago, biodynamic viticulture could be shrugged off as “some dogma about phases of the moon and cow horns.” But now that we find a who’s who of the wine world on the member lists of relevant biodynamic organizations, it’s no longer so easy to cancel adherents to this form of farming. Those…...

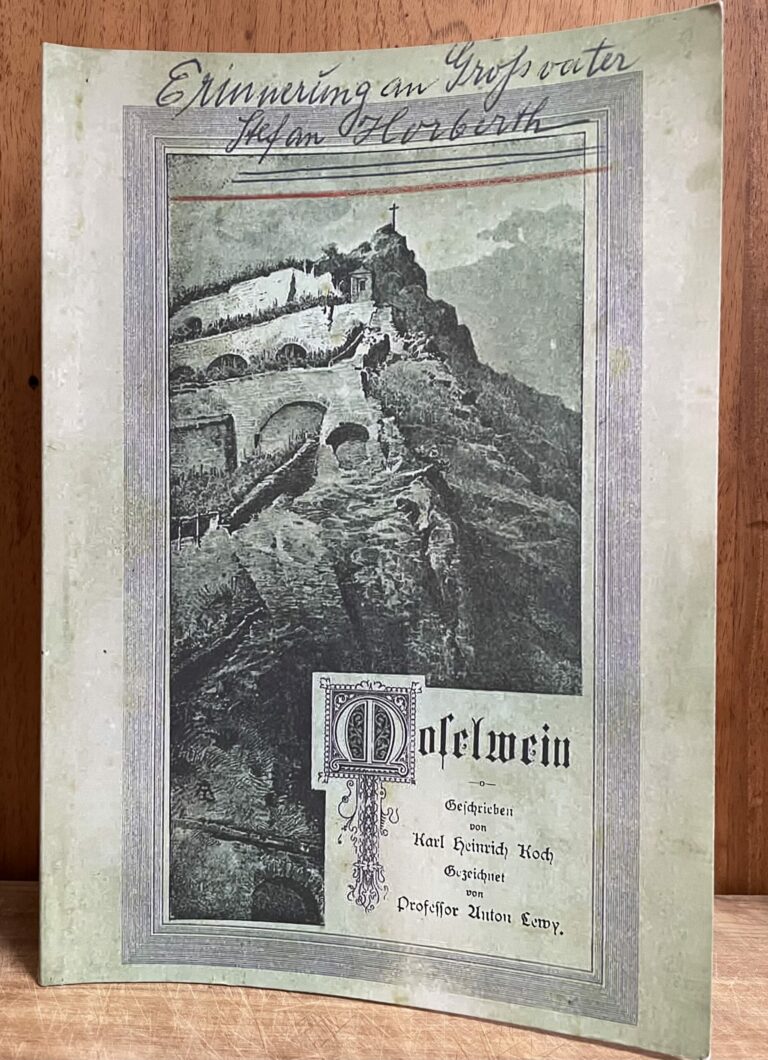

We like to think of Mosel wine as eternally glorious. The river valley’s nearly 2,000-year vinous history, its relics of Roman civilization and tributes to Celtic wine gods, its very viticulture carved with seeming permanence into stony banks all suggest an unbroken line. But an excellent new book, edited by Lars Carlberg, with able assistance from David Schildknecht, Kevin Goldberg, and Per Linder, underscores the extent to which the Mosel’s glory has been far more ebb than flow. Such awareness only makes the late 19th-century golden age that is the book’s focus more luminous. The book nests together several components…....

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today