Rainer Zierock: Visionary Provocateur

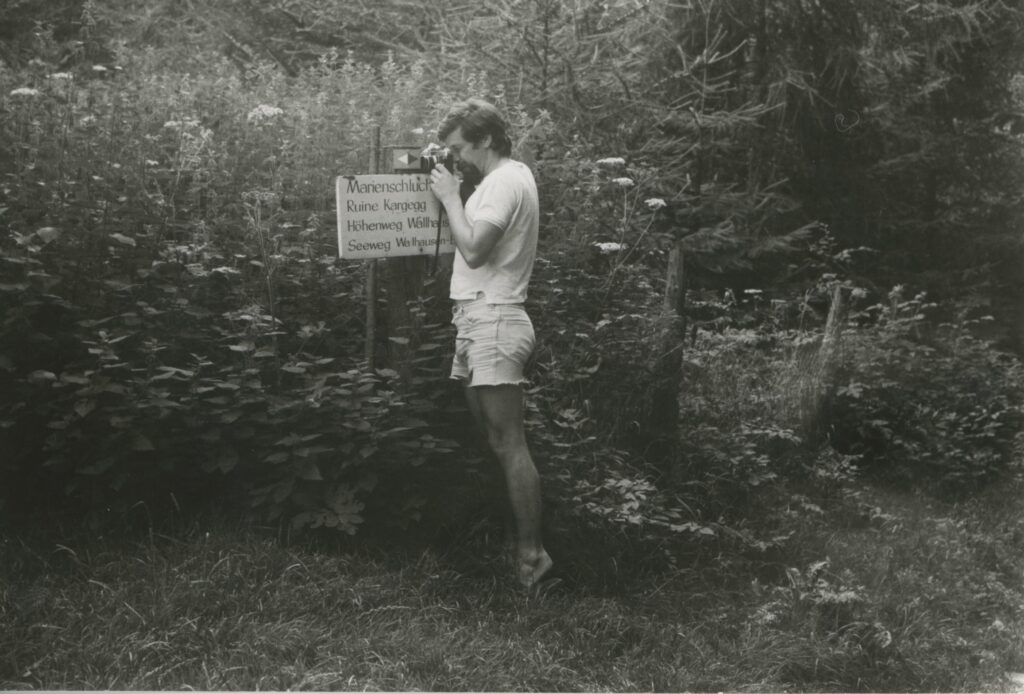

If Emilio Zierock finds it hard to talk about his controversial father, you can’t tell by listening to him. He speaks with remarkable openness about the man. Rainer Zierock, who passed away in 2009, was a brilliant visionary, but also in all likelihood the grandest provocateur in post-war German and Italian viticulture. The powerfully eloquent and often choleric Zierock was considered an eccentric of note, and one who went after everyone. More than a few people also consider him a misunderstood genius, far ahead of his time. His influence on the young wine generation, and particularly the natural wine scene,…