Reimagining Pannonia

A map of vanished Pannonian wine culture is beginning to reemerge with regional heroes such as Roland Velich and Tamás Kis leading the way.

A map of vanished Pannonian wine culture is beginning to reemerge with regional heroes such as Roland Velich and Tamás Kis leading the way.

Rainer Schäfer writes about what he values most: wine, food, and soccer. The first wine that impressed him as a teenager was a Silvaner from Endingen, grown in the vineyard of his Kaiserstühl relatives. He's lived in Hamburg for 30 years and travels the wine regions of the world, always curious about dazzling personalities, surprising experiences, and unknown pleasures.

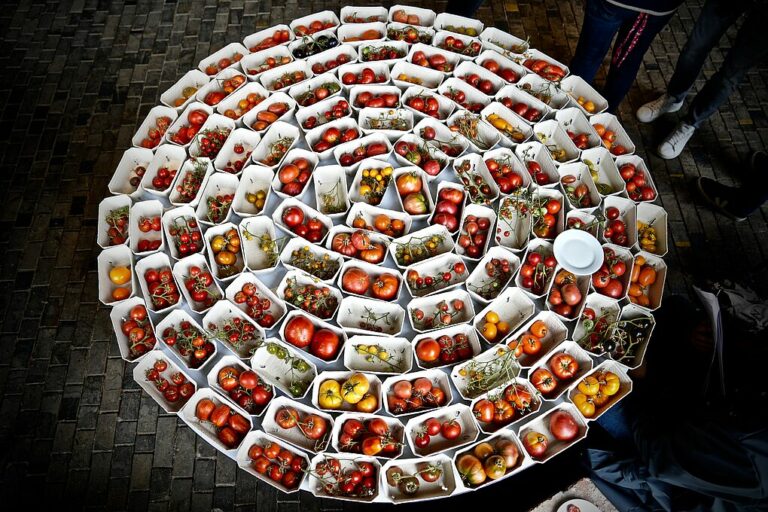

Calling from the expansive, flat landscape that forms the western edge of the Pannonian Puszta steppe flatlands, Erich Stekovics is a lone voice in the tomato world. Where others seek high yield and hardy reliability, Stekovics makes the case for flavor and site. He and his wife Priska belong to the tiny share of Austrian farmers cultivating tomatoes without the cover of glass or foil, and without irrigation. At the eponymous estate in Frauenkirchen, the pair cultivate and safeguard several thousand varieties in the open, and in addition to chili peppers, onions, and garlic, their fields are surrounded by vines…....

Wine regions are threaded along the Danube, one after another, like a string of Chanel pearls. Wagram, Kamptal, Kremstal, Wachau. And Traisental — the only one that lies exclusively south of the Danube. Its namesake river, the Traisen, divides the valley as the Seine does Paris or the Gironde does Bordeaux, into left and right banks. The tiny region flaunts French finesse and cool avant-garde. But also a rustic, down-to-earth charm. In Paris, the Left Bank is the quartier of intellectuals and artists. Through Yves Saint Laurent it achieved world fame in fashion. Who or what sets the tone and…...

The world of sparkling wines is changing for the better. The number of producers approaching this beverage in serious, artisanal, and creative ways continues to climb. “Grower Sekt” from Austria and Germany is very much en vogue. We are witnessing a tremendous push to quality. For a long time, “mass over class” was the motto, especially in Germany. But for a new generation, awareness of terroir and a trend toward reducing residual sugar are increasingly the focus. No stone has been left unturned in Austria, either. For several years, Austrian Sekt has been governed by a three-tiered quality pyramid: “Sekt…...

Gerhild Burkhard, founder of the International Sparkling Festival, reveals everything you've always wanted to know about sekt (*but were afraid to ask).

My first true Blaufränkisch moment came in 2013, at a now-shuttered restaurant in Hamburg. Thirty-six bottles from a swath of Austria’s appellations stood open for tasting, from classics like Prieler’s Goldberg 1995 to Marienthal from Ernst Triebaumer to Ried Point from Kolwentz. Those wines impressed me, as they had in the past, even as they failed to inspire me. This time, however, other wines had joined the lineup. The Spitzerberg of Muhr-van der Niepoort (today Weingut Dorli Muhr) , for example; the 2010 Reserve Pfarrgarten from Wachter-Wiesler; and the 2002 Lutzmannsburg Alte Reben from Moric. Suddenly, I was electrified. The wine in the glass was entirely unlike anything I…...

12/17/2021 Wines with a View at Winkler-Hermaden By Jill Barth The story of Weingut Winkler-Hermaden and its home in a striking 11th-century castle starts with a “small, tough” woman. That woman, Magdalene Helene, was current proprietor Georg Winkler-Hermaden’s grandmother. When he found her diary, which she kept from her arrival at the Schloss Kapfenstein in 1916 through WWII, he “began to read and couldn’t stop until the book was finished.” In 1916, Magdalene Helene came to the castle as a young woman to work as a maid. Just two years later, her employer died and bequeathed the Schloss and…...

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today