Rotling Outlaws

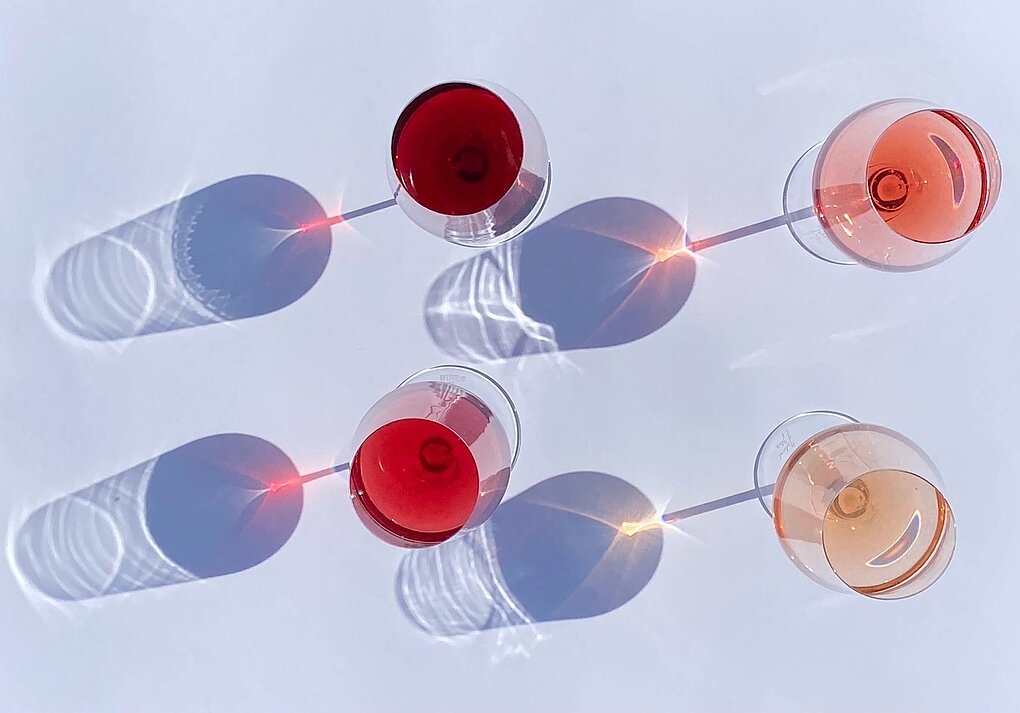

The sun blazes. The air shimmers. On the horizon four figures throw long shadows across the dry, crumbling ground. They are headed toward a city. Doors swing open. The four step from light into dark, their throats dusty and dry. Behind a deserted bar stands a man. He pushes four full glasses over to them. Out of the glasses sloshes a wine as red as the setting sun. If you aren’t thirsty by now, you should at least be hearing the melody of a harmonica. This is how the opening scene of a revival—the Rotling revival—could begin. The four men…