Weingut Heinrich: Finding Freedom in Less

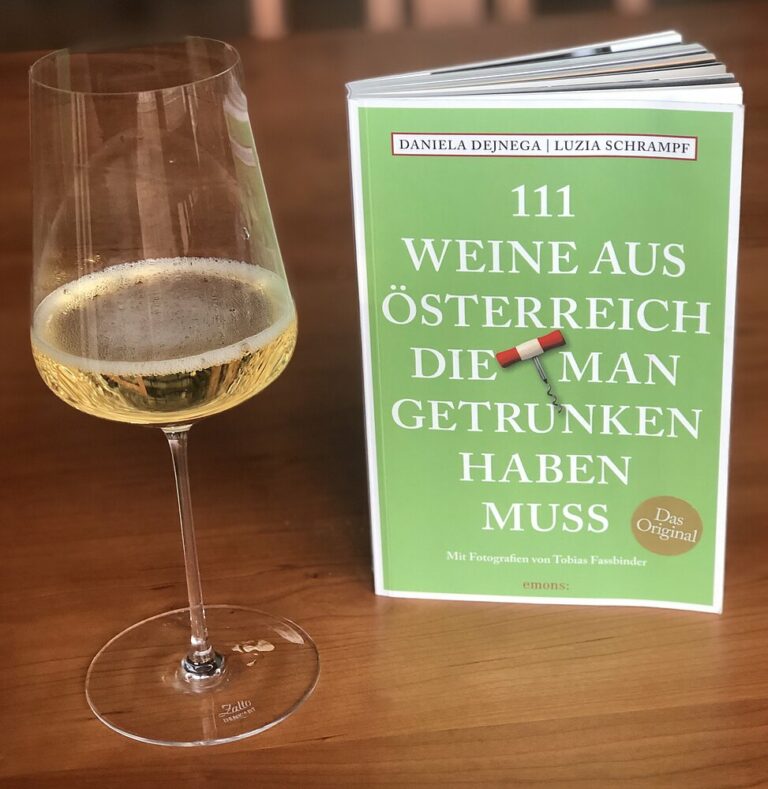

It takes little to be happy. And he who is happy is king.” This 19th-century German song – with just two lines – expresses how good a simple life, with little, can be. Just how little is something each of us has experienced, almost daily, this year. Finding the joy in this can be difficult, and regrettably few have managed to perceive the freedom in “less.” Two people who did so long ago are Heike und Gernot Heinrich of Weingut Heinrich in Austria’s Burgenland. I visited them in early September, during Europe’s pandemic lull. The timing couldn’t have been better….