Franken Casks the First Stone

Silvaner aged in shell limestone casks: quintessential expression of terroir, steinwein 2.0, or a flight of foolishness?

Silvaner aged in shell limestone casks: quintessential expression of terroir, steinwein 2.0, or a flight of foolishness?

Matthias Neske has done a lot of things. He has worked for the government, in research, in tourism, has done UN projects in Asia, holds a PhD in Geography - and then there's wine.

Now he works full time as a freelancer in the wine business. He has been publishing on his blog Chez Matze for over ten years. He is also co-author of the Falstaff Wine Guide Germany, and writes for retailers and growers. Matthias is passionate about individuality, nature, diversity and dry humor.

We’ll come right out and say it: Franken (Franconia) is Germany’s most underrated region. If you still think of it as the source of wan wines poured from squat flagons and drunk mostly at home, we’re here to let you in on a secret: there has never been a more exciting time for this corner of northern Bavaria, where wine, not beer, rules the day. The region sits just below the 50th parallel and at the cool, eastern edge of Germany’s wine core. It’s a perilous position for viticulture. As decades of frost-crimped and extreme-heat-affected vintages attest, its starkly continental…...

My first true Blaufränkisch moment came in 2013, at a now-shuttered restaurant in Hamburg. Thirty-six bottles from a swath of Austria’s appellations stood open for tasting, from classics like Prieler’s Goldberg 1995 to Marienthal from Ernst Triebaumer to Ried Point from Kolwentz. Those wines impressed me, as they had in the past, even as they failed to inspire me. This time, however, other wines had joined the lineup. The Spitzerberg of Muhr-van der Niepoort (today Weingut Dorli Muhr) , for example; the 2010 Reserve Pfarrgarten from Wachter-Wiesler; and the 2002 Lutzmannsburg Alte Reben from Moric. Suddenly, I was electrified. The wine in the glass was entirely unlike anything I…...

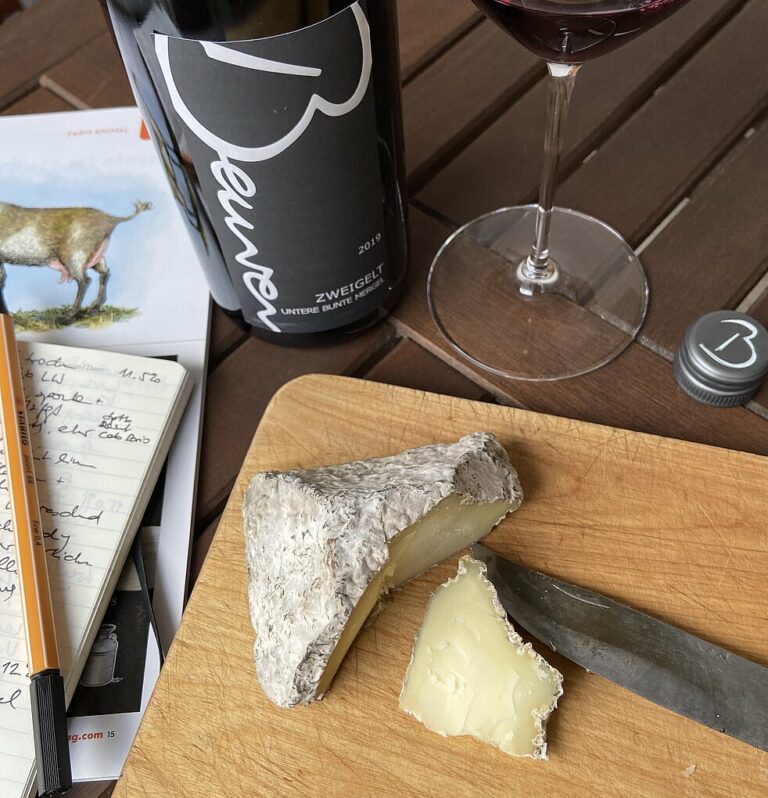

Screwcaps for fine wine are making a comeback. Do these cheap and cheerful closures have what it takes for the long run?

When Westphalia and Württemberg meet on the table good tastes are bound to happen.

What do one of the Mosel’s oldest winemaking estates and a country with a fledgling wine-drinking culture have in common? The answer, as with most things in life, is Riesling. “German Riesling has become a synonym for white wine in Finland,”” says Heidi Mäkinen MW, Portfolio Manager for Viinitie Oy, one of that country’s largest importers of German wine. “Finns like the freshness and fruit, and Riesling is one of those wine words that’s incredibly easy to pronounce.” As Viinitie’s new portfolio manager, Mäkinen, for whom work and private life has little separation, has kicked off her holidays 2,000 kilometers south of her…...

On an early autumn night, in a quietly insiderish neighborhood of Queens, New York, deep beats and warping, hypnotic sound penetrate the stillness. Trapezoids of light slant onto the dark sidewalk through the broad windows of a corner restaurant, the music’s source. Silhouetted figures mingle and shift in projection. Robert Dentice, noted collector of Riesling and vinyl, stands near the door, a bottle of Keller Abts E — one of Germany’s, if not the world’s, most coveted wines — in hand, greeting new arrivals with hugs and heavy pours. Inside, there’s an invitingly louche aura of fin-de-siècle Vienna or Berlin. A slew of wine is open, almost…...

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today