On the Way to German Chardonnay 2.0

German Chardonnay may be the most thrilling wine for our moment.

German Chardonnay may be the most thrilling wine for our moment.

Christoph Raffelt is one of an exciting new vanguard of voices when it comes to German wine. And voices is not a euphemism here, as it is indeed his voice together with his stellar cast of winemakers and guests that come together on his monthly podcast Originalverkorkt.de; while his words appear in his online magazine of the same name. He's been on the road since 2016 with Büro für Wein & Kommunikation as a freelance journalist, copywriter and all-round wordsmith. His work has appeared in such esteemed publications as Meiningers, Weinwirtschaft, Weinwelt, Sommelier, Champagne-Magazin and Schluck.

for S.B. with love Die Rebe ist ein Sonnenkind. Sie liebt den Berg und haβt den Wind.So open your door already—for god’s sake, just let me in! Nothing to fear from wild slopes—a matter of terraces and grading.Sankt Aldegund, your roses—they labor on unforgiving slate. Vigor derives from parameters. The desert ends with water.Ritual is an amphora: it gives life room to breathe. The hag at the door is never a hag—she’s always a secret queen. Don’t you fear that ugly mug comes bringing revelation. The special red plum from the Mosel is imbued with healing power.If you go to the…...

Pinot Blanc is neither a distinctive cépage nor a particular grape variety – at least, not from the viewpoint of ampelography or genetics. And what there is of pure Pinot Blanc worldwide is nearly all rendered in German-speaking growing regions where it is typically known as Weissburgunder.

Sammie Steinmetz is one half of Weingut Günther Steinmetz, a mid-sized, family-run winery in Brauneberg on the Mosel. Born in Pensacola, Florida, Sammie came to Germany in 2007 as an enlisted member of the U.S. Air Force, stationed at Spangdahlem Air Base not far from the winery. She’d already planned on settling in the country when her term of service ended (“because Riesling,” she laughs). But a chance invitation to a wine-tasting introduced her to fifth-generation winemaker Stefan Steinmetz. Two weeks after meeting, they were dating and they married a few years later. In 2014, Sammie took early retirement from the…...

“When I started drinking wine, wine was French,” my father told me recently over dinner at Scheepskameel, a Dutch restaurant known for its excellent wine menu. He never spends more than 10 euro on a bottle, and rarely drinks white, but that evening he unexpectedly admitted, he preferred our glass of German Riesling to our bottle of red Bordeaux. A few days later, I hosted a Riesling tasting for some serious wine friends. They have accounts with posh traders and their own cellars, which are typically stocked with Burgundies and Bordeaux. They were impressed. But, I wondered, would they buy…...

The one piece of German wine law I thought I fully understood was the Prädikat system. First, I memorized the Prädikat levels. Later, I memorized the minimum must weights. I pushed aside my frustration that the sweetness of a wine did not correspond with Prädikat level — accepting that residual sugar wasn’t part of the system. Before visiting Germany, I never expected that the lack of consistency in sweetness for Prädikat wines would be an ongoing point of tension in the very country that came up with the system. Or, that by prioritizing origin over Oechsle degrees, Germany’s renowned wine organization Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter (VDP) would in essence dismiss the…...

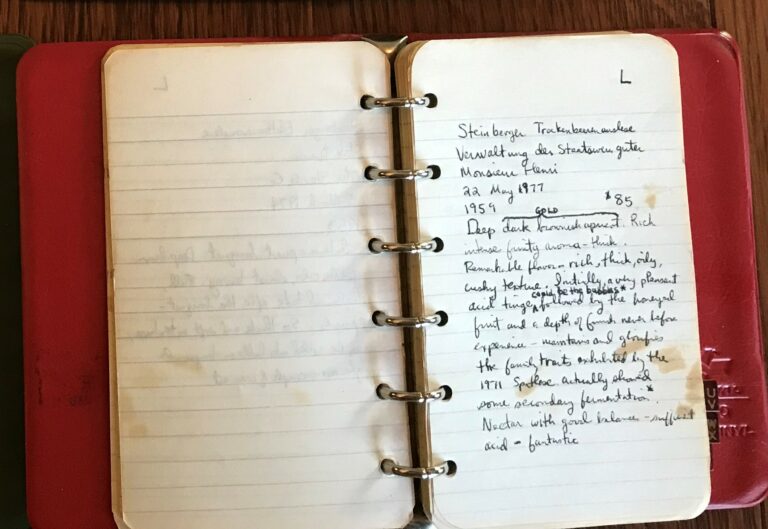

My twenty-something self left two gifts for the older man I would become: a doctorate in applied mathematics and four small, looseleaf notebooks. The degree opened many doors and reinforced my ability to do independent research, perform analyses, and document the results. The notebooks, along with labels from many of the bottles, form an archive of my first decade tasting wine. Between 1969 and 1979, a period covering my student and early career years, I kept detailed notes on almost everything I tasted. During most of that time, I lived in Evanston, Illinois. It was dry until 1975, necessitating runs…...

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today