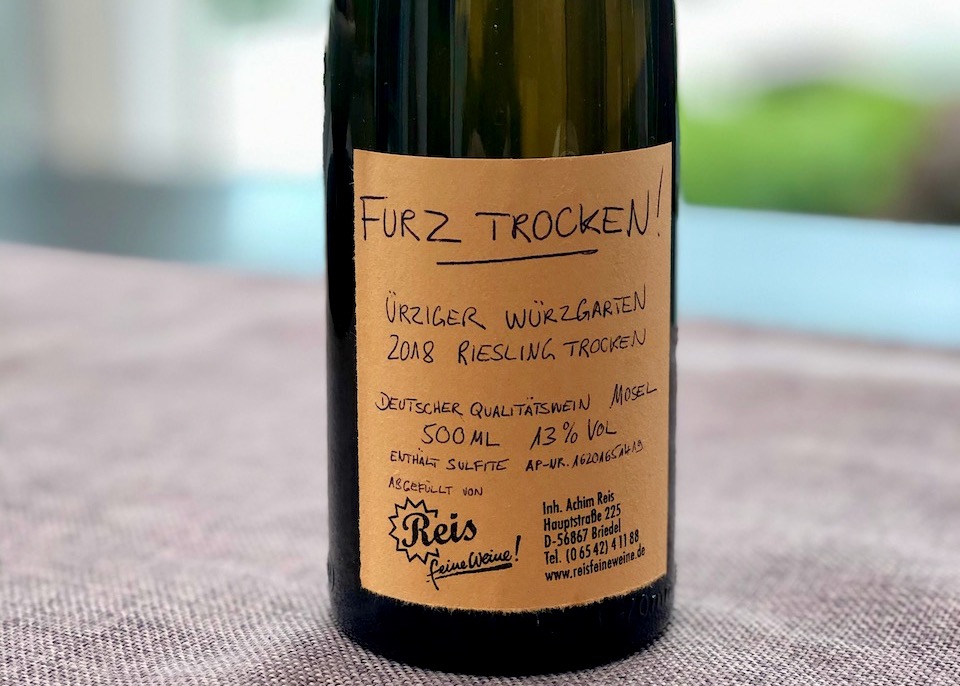

What’s German for Drier Than Dry? Furztrocken, of course

The dark wit of Berlin. Dangerously low water levels in the Rhine River. Black bread. Germany does trocken like few others. And then there’s the wine. Despite its reputation as the land of Blue Nun, more than 60 percent of the wines made in Germany are dry. And within that 60 percent, there are discernible levels of dry, drier, and driest. So dry, in fact, that there’s a strangely specific word for it. (Of course there’s a word. It’s Germany. There’s always a word.) Furztrocken. Fart Dry. Literally. As difficult to grasp as I find a term like feinherb, it’s Kinderspiel when compared to furztrocken. Then again, mindset…