What Does It Mean to “Be VDP”?

The historic German wine club faces a crossroads.

The historic German wine club faces a crossroads.

Writer, Editor, Publisher

Valerie Kathawala specializes in the wines of Germany, Austria, South Tyrol, and Switzerland, as well as those closer to her home in New York City. Her work appears in the pages of Noble Rot, Full Pour, SevenFifty Daily, Meininger’s Wine Business International, Pipette, Glug, Pellicle, and a number of other tolerant publications.

Djuce first entered my periphery late last year at the New York City iteration of Karakterre’s natural wine fair. Amid a cheerful invasion of producers from what has winningly been dubbed “the Austro-Hipsterian Empire,” I narrowed my focus to taste at some touchstones of Austrian natural wine — Judith Beck, Zillinger, Heinrich, Meinklang, Nittnaus, Weninger. Hurrying between offerings of electric-amped Grüner Veltliner and ethereal Blaufränkisch, I brushed by a small table stacked with slim, colorful cans and a paper sign that read “Djuce.” I paused just long enough to register an internal eye roll at what I assumed was the bro-culture spelling and reflexive ecoism of yet…...

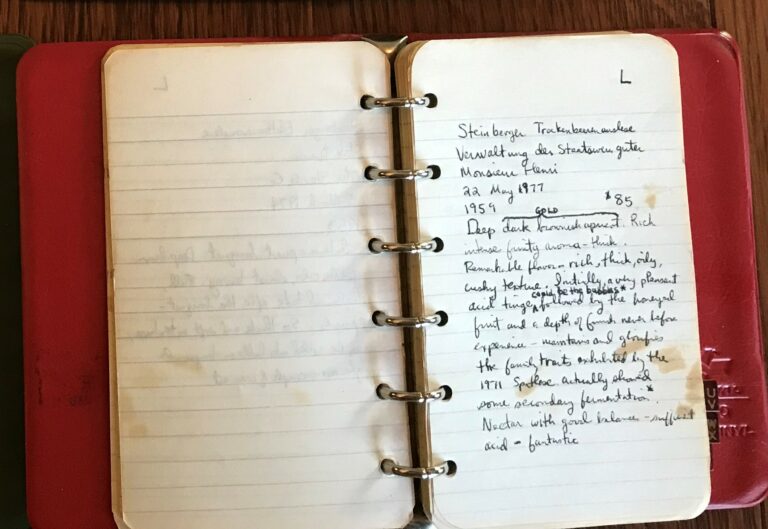

My twenty-something self left two gifts for the older man I would become: a doctorate in applied mathematics and four small, looseleaf notebooks. The degree opened many doors and reinforced my ability to do independent research, perform analyses, and document the results. The notebooks, along with labels from many of the bottles, form an archive of my first decade tasting wine. Between 1969 and 1979, a period covering my student and early career years, I kept detailed notes on almost everything I tasted. During most of that time, I lived in Evanston, Illinois. It was dry until 1975, necessitating runs…...

How catastrophe proved a catalyst for change, and helped Germany’s Pinot paradise find a new way to farm.

Winemakers in the Mosel are tending an old tradition that is budding anew. These modern Pinots reach for elegance and complexity, edginess and vitality. and the world is finally taking notice.

The sun blazes. The air shimmers. On the horizon four figures throw long shadows across the dry, crumbling ground. They are headed toward a city. Doors swing open. The four step from light into dark, their throats dusty and dry. Behind a deserted bar stands a man. He pushes four full glasses over to them. Out of the glasses sloshes a wine as red as the setting sun. If you aren’t thirsty by now, you should at least be hearing the melody of a harmonica. This is how the opening scene of a revival—the Rotling revival—could begin. The four men…...

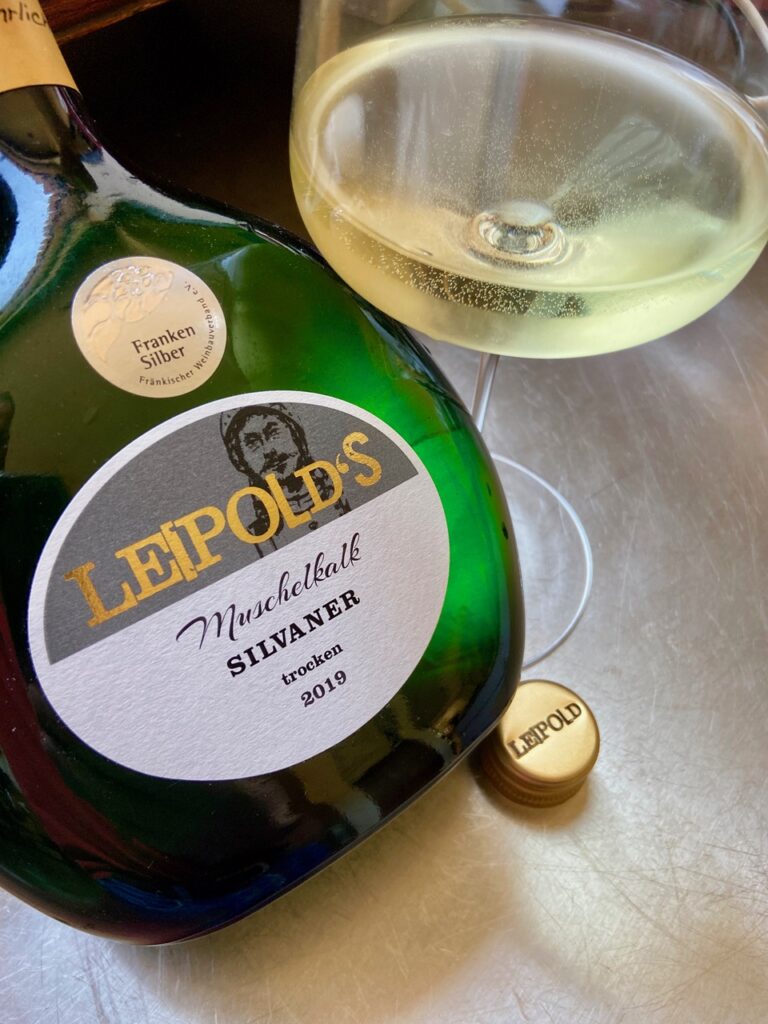

Confession time: Which wine and food pairings make your eyes roll faster than a teenager’s? Champagne and strawberries? Pizza and Lambrusco? Muscadet and oysters? In southern Germany, Silvaner and white asparagus are regional marketing 101. Silvaner has been praised and prized as a pairing for the spring stalk to such an extent that grocers will double their inventories of cheap Silvaner and stack it by the case in the vegetable section. And while the fastest way to get a screenful of Internet ill-will slung in your direction is to suggest the pairing to a German wine group, it is true…...

Enjoy unlimited access to TRINK! | Subscribe Today